Just a few miles from the US border in the Mexican city of Tijuana, an innovative education program is making sure migrant children don’t miss out on learning.

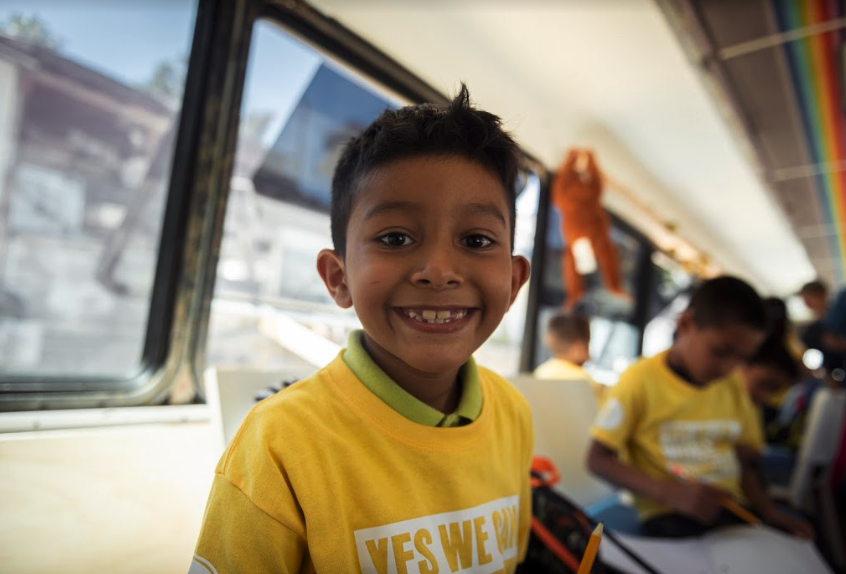

Over the past three weeks, the Yes We Can World Foundation has enrolled 30 children — ages 5 to 12 — in its new initiative that runs out of a bus-turned-classroom.

Most of the children are from families fleeing violence and poverty, who have been staying in shelters for weeks or months while waiting to apply for asylum in the US. In the meantime, Yes We Can’s free program offers specialized bilingual education for the children who tend to have low literacy and struggle with social skills. The bus seats 80 children and in a few weeks, the program will accept another 20 students.

Yes We Can accepts all children, regardless of their citizenship status, according to its director and founder, Estefania Rebellon. The program provides each student with a backpack, school supplies, t-shirts, and later this month, shoes, Rebellon told Global Citizen.

The school’s staff has experience working with displaced children in Latin America. For many children, the program is their first introduction to English, and Rebellon is looking to add more teachers who speak Indigenous languages.

Many of Yes We Can’s students come from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and the Mexican states of Guerrero and Michoacan. Their families are seeking safety and security for various reasons, from escaping high levels of crime caused by drug cartels to domestic violence.

For one family, their child hadn’t been in school for more than five months while waiting for asylum status. A lot of children have to stop their education and start working to provide for their families, and Yes We Can is the first time they’ve attended school full-time, Rebellon explained.

Read More: UN Human Rights Chief Blasts Dire Conditions for Migrants at US Border

Children seeking asylum face many challenges, she said.

“There’s definitely a turmoil in their emotional well-being of missing home and not really being aware or prepared for what they’re going through,” Rebellon added. “A lot of the children are in a state of confusion.”

During one recent exercise, Rebellon said some students started drawing their dogs and family members that they miss.

Without support, conflict-affected children lose out on the chance to reach their full potential and rebuild their communities. Children in conflict-affected countries are more than twice as likely to be out of school compared to those in countries not affected by conflict, according to UNESCO.

But parents reported that they’re already seeing positive changes in their children since they started at Yes We Can. Before enrolling in the program, parents reported to Rebellon that their children had trouble sleeping and controlling their anger. Now they have something else to focus on: education.

Read More: Floating Schools Help These Bangladeshi Students Learn During Monsoon Season

One mother told Rebellon this is the first time she felt safe sending her children to a school where she didn’t have to worry about kidnappings or a shooting happening. Another said her child is motivated to go to class now, whereas back home, she had to force them to go.

“We’re trying to do our best to make this accessible for them and not have any obstacles that prevent them from going to school and having an education,” Rebellon said.

She has seen students’ emotional well-being improve, along with their attention, sense of trust, and writing skills. The program also aims to help children feel they are building a community through different activities, such as having them help paint the bus’ walls.

Also an actress, Rebellon started Yes We Can because she was a migrant child herself. She came to the US from Colombia when she was 10 years old to escape death threats made against her father, and school helped her overcome a lot of challenges. Ultimately the “tiny home movement” inspired her to convert the bus into a school, according to Reuters.

Rebellon hopes to provide this program on the US side of the border, too, and eventually launch an education program for teenagers that operates out of tents outside of shelters.