Eighteen years ago, Michael Smith — who goes by Zaki — was arrested for the last time.

After a lifetime of going back and forth to prison, he decided that he would never let himself be in this position again.

Smith was charged with committing fraud, stealing checks, and cashing those checks. He was sentenced to 36 months.

“Literally when they put the handcuffs on me, I knew I was not going back to prison after this,” he told Global Citizen.

“Isn’t that cruel and unusual punishment?”

And he didn’t. But what no one told him is that once those 36 months were up, he’d still be serving a life sentence — albeit of a different kind.

“No one ever tells you about it in court … No one says: You have 36 months, but after you finish those 36 months, for the rest of your life, you will now be ostracized from employment, housing, licensing, schooling, and the 47,000 other laws that come with collateral consequences and this perpetual punishment,” Smith said.

"Isn’t that an Eighth Amendment violation? Isn’t that cruel and unusual punishment?”

The term “collateral consequences” is a relatively new one for Smith. It refers to the many legal restrictions people who have been convicted of a crime face that prevent them from gaining certain kinds of employment and benefits, including housing and education support. These laws may also render people ineligible for certain licenses, including specialized permits and licenses to operate businesses.

And though he had experienced them before, Smith, a barber, never knew there was an acknowledged name or reason for the many challenges he had faced trying to re-enter society after being incarcerated.

It wasn’t until he lost his job last March that Smith learned it wasn’t just systemic racism or the failure of the government that had held him back. It wasn’t simply that, as a black man who grew up in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood during the “crack era,” the odds had been stacked against him from the start.

Smith discovered that there are tens of thousands of laws on the books keeping him and other formerly incarcerated people across the United States from getting back on their feet after being released from jails and prisons — and now he’s determined to overturn those laws.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith sits on the steps in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn. Today the neighborhood is home to trendy restaurants, but when Zaki was growing up, the area saw high rates of violence, drug use, and poverty.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith sits on the steps in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn. Today the neighborhood is home to trendy restaurants, but when Zaki was growing up, the area saw high rates of violence, drug use, and poverty.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith sits on the steps in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn. Today the neighborhood is home to trendy restaurants, but when Zaki was growing up, the area saw high rates of violence, drug use, and poverty.

Since being released from prison in July 2004, Smith has been working with young people, hoping to provide the guidance and mentorship that had been absent from his life as a child and teen, which he believes contributed to his actions and involvement with the criminal justice system later in life.

“Initially it just started with me just telling them my story,” Smith said. “Like where I come from, what my experiences was, the hurt, the pain, the obstacles and how I still stand resilient and am overcoming those obstacles.”

And when he was released from prison, he was even more committed to empowering and supporting youth so that they might never experience his situation.

His employer, the Future Project, was also aware of his criminal record.

And five years ago, through a connection he made while working at a barber shop, he began working with students through the Future Project, a nonprofit that works to empower young people to build a better future.

The Future Project hired him as a “dream director” to work in East Side High School in Newark, New Jersey, “to inspire the passion and purpose of young people.” And it seemed like the perfect fit, a place where he could use his past experience and his skills to help motivate students.

Smith initially kept cutting hair on the side, and said that being a barber and working with young people are things he loves to do equally. But the latter eventually required most of his time and all of his passion.

At East Side High School, Smith took over what was once the detention room and brought in an artist to work with the students to create murals and transform the space into a “safe haven” where anything was possible, he said. The school became his home, and its staff and students — who he said knew of his criminal record, but accepted and supported him — became like family.

His employer, the Future Project, was also aware of his criminal record. So when Smith was asked to submit to routine fingerprinting in December 2017, he did so without hesitation.

Last year, Michael 'Zaki' Smith lost his job working with youth in New Jersey, despite support from their school's administration. The state does not allow people with felony convictions to work in schools, a 'collateral consequence' of incarceration.

Last year, Michael 'Zaki' Smith lost his job working with youth in New Jersey, despite support from their school's administration. The state does not allow people with felony convictions to work in schools, a 'collateral consequence' of incarceration.

Last year, Michael 'Zaki' Smith lost his job working with youth in New Jersey, despite support from their school's administration. The state does not allow people with felony convictions to work in schools, a 'collateral consequence' of incarceration.

Shortly after, he received a letter from New Jersey’s Department of Education. He had been permanently disqualified from working in schools in the state.

“And I’m like … Hey, wait a minute — I’ve been out 15 years and working with young people since. My principal is cool with [my record], the superintendents, all the kids that I’ve been working with,” Smith recalled.

“It just wasn’t even human. There was no human connection to the system.”

It was in the process of trying to appeal the state’s decision, with the support of his school’s administration, that Smith learned about collateral consequences.

“I came across this phrase … this legal jargon called ‘collateral consequences,’ and it pretty much blew me away,” Smith said. “Collateral consequences are essentially a silent sentence of perpetual punishment long after your sentence is done.”

Smith read about a case in which a Honduran immigrant, José Padilla, who had lived in the US for 40 years, had been advised to plead guilty to a crime in Kentucky, without being told that he could be deported as a result. Padilla argued that his Sixth Amendment rights had been violated because he had not been advised of all the consequences of pleading guilty. And while the Supreme Court found that defense attorneys must inform their clients of the deportation consequences of plea agreements, it remains unclear whether or not they should inform defendants of all the collateral consequences associated with their guilty pleas.

In Alabama, a person with a felony conviction is ineligible to become a therapy dog handler.

Smith said they should, but the reality is that doing so wouldn’t actually change the outcome for most. Whether or not they were told beforehand, any formerly incarcerated person convicted of crimes would likely still have to deal with these collateral consequences and forewarning them of this “life sentence” won’t change that fact.

Instead, Smith said we need to overturn these laws, one by one, state by state.

“I've just been in this space pursuing the whole abolishing of collateral consequences and specifically looking in the spaces of employment, housing, licensing, and schooling — essentially the things that will help assist an individual in never returning back to prison,” he said.

The federal and state laws that place restrictions on formerly incarcerated people after they are released from prison — as well as people with criminal records who have not been incarcerated — range from broad to absurdly specific.

In Alabama, a person with a felony conviction is ineligible to become a therapy dog handler. A person with a felony or misdemeanor on their record cannot register as an interior designer in Wisconsin. Having a felony record in Florida makes a person ineligible to serve on the board of their condominium.

“My belief is that collateral consequences — this perpetual punishment — is the heartbeat of recidivism.”

However, many collateral consequences coded into law have a wider, more damaging impact.

In all but two states, people convicted of a felony are stripped of their right to vote while incarcerated, and in 12 states, they can lose this right permanently. People with criminal records are also ineligible for food stamps and other forms of public assistance in many, including New York, New Jersey, and Texas.

Formerly incarcerated people and people with criminal convictions who have never been incarcerated may be ineligible for housing assistance and are shut out of a large swath of employment opportunities.

These collateral consequences can be especially devastating for formerly incarcerated people trying to re-enter their communities. These laws can create a cycle of poverty and struggle that drives people to re-engage in criminal activity and, potentially, to become incarcerated again.

“My belief is that collateral consequences — this perpetual punishment — is the heartbeat of recidivism,” Smith said, referring to the term for re-incarceration.

“Like, if I can't work [and] no one will allow me to live in a place or I can't get a license … more than likely, I may have to return back to what I did to get me in prison in the first place,” he said.

Just 55% of formerly incarcerated people report any earnings in their first year after release. Only about 20% of those who do earn more than $15,000, which is about how much one would make working full-time making the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, according to the Brookings Institution.

People who received vocational training while incarcerated or performed certain jobs while incarcerated — like California’s inmate firefighters who receive training from the state — are often not eligible for those same jobs upon release.

“These are foolish laws because the state is depriving itself of people who can become highly contributing members of society,” said Ames Grawert, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

The US as a whole is losing a lot of money because of collateral consequences. These laws barring formerly incarcerated people and people with criminal records from employment cause the US economy to lose between $78 and $87 billion every year, according to the Center for Economic Policy and Research.

But these consequences and policies are particularly costly for communities of color and low-income communities, which are often one and the same. So while $87 billion is a staggering amount of money, Grawert said the actual cost could be worse.

“As a kid, I remember going out shoplifting with my mom.”

“Incarceration preys on lower-income communities to begin with. So these are people who aren’t making a particularly large amount of money. Now, think about what that does to their ability to accumulate wealth to pass on their children,” he said.

“Suddenly you're looking at the impoverishment of entire communities over the course of generations.”

Smith describes his upbringing as one that lacked structure and the support of adults due to circumstance. He grew up in Brooklyn during the ’80s and ’90s, a time of frequent crime, violence, and drug use.

Drugs were a mainstay of his household and incarceration was the norm in his family. Smith said all of his uncles and all but one of his aunts has been to prison at some point.

“As a kid, I remember going out shoplifting with my mom,” said Smith, whose mother had him around the age of 15.

“She worked with what she thought would yield the best results for her, being a young single mom,” he explained. He added that today she is clean, sober, married, and “doing all the greatest things in the world, which is a beautiful thing to see.”

His story was pretty much everyone’s story in his community, he said. And inside prison, it didn’t look much different.

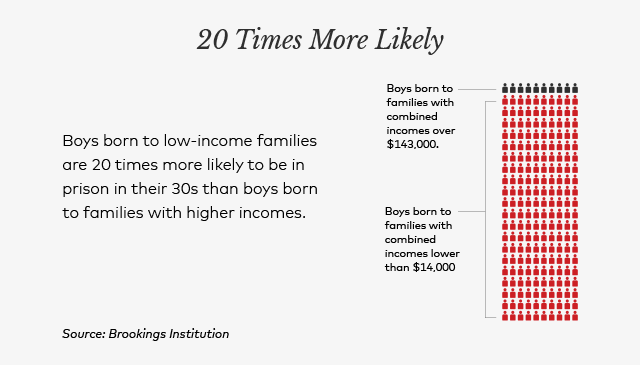

“When you look at who is in the prisons in this country, the majority come from poor neighborhoods with high violence and a lack of resources,” Smith said.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith at Miracles Barber Shop in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, where he used to work. Zaki still occasionally cuts hair, but is now focused on his work as an activist raising awareness about the collateral consequences of incarceration.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith at Miracles Barber Shop in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, where he used to work. Zaki still occasionally cuts hair, but is now focused on his work as an activist raising awareness about the collateral consequences of incarceration.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith at Miracles Barber Shop in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, where he used to work. Zaki still occasionally cuts hair, but is now focused on his work as an activist raising awareness about the collateral consequences of incarceration.

And these same communities are the ones that tend to be more heavily policed, leading to more frequent arrests and greater incarceration.

People of color make up a disproportionately large percentage of the incarcerated population in the US. Black Americans account for 40% of the country’s incarcerated population, but make up just 13% of its general population, according to the Prison Policy Institute. And incarcerated people are disproportionately poor in comparison to the US population at large.

This is not particularly surprising given that people of color experience poverty at higher rates, whether incarcerated or not. But it is alarming because the justice system criminalizes people living in poverty on their way into the system in multiple ways, and then punishes them again on the way out.

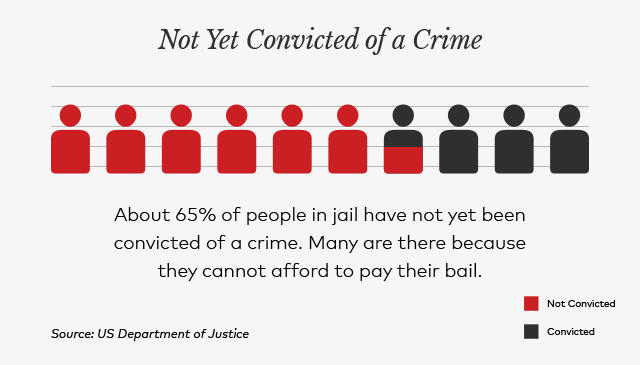

The cash bail system, for example, keeps people who have not yet been convicted of crimes in jail because they cannot afford their freedom. The system was originally created as leverage to ensure that people charged with crimes would attend their court dates. However, in practice, experts say the system now penalizes people simply for being poor.

Approximately 65% of people in jail have not yet been convicted of a crime, according to the US Department of Justice. Many are there because they cannot afford to pay their bail.

“We really have one system of justice of the wealthy and one system for the poor — and that is critical to acknowledge if we want to fix the justice system,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Not being able to make bail and remaining in pre-trial detention means that people are taken out of their communities for days, weeks, and sometimes years, before being convicted. During this time, they are away from their families, unable to work, and have a more difficult time participating in their case, often leading to worse legal outcomes and harsher sentences.

“I came from the back with my orange jumpsuit on with a public defender.”

The last time he was arrested, when Smith was charged with three different crimes, his bail was set at over $400,000.

“It was ridiculous … It just didn’t make sense at all,” he said. “I knew there was no way I was paying that at all. My family had no assets or anything to put up like houses. So I just psychologically and emotionally scratched that out, and just knew like … I’m going to be here.”

Smith spent about 23 months in jail, fighting his case, before taking a guilty plea agreement and being sentenced. In that time, his wife gave birth to his fourth child. And because he was not working or physically present in their household, he was not able to help support his family during this time.

Smith wasn’t the only one charged in his case — but he was the only one who served time for it. Smith said being able to afford bail made a difference to these legal outcomes “without a question.”

“My co-defendants, who did not look like me, had the means [to make bail] and they walked in with their suits on and their paid attorneys and fought the case and never went to prison — never seen a day in [jail] other than the arrest,” he recalled.

“I came from the back with my orange jumpsuit on with a public defender,” he recalled.

Smith admits he was guilty. He had no illusions about being let go; his only goal was to negotiate a sentence that wasn’t overly harsh. But many who are wrongfully charged and unable to pay their bail do plead guilty to crimes they did not commit in hopes of being released sooner.

Fighting a case can take time, and depending on the case, it can stretch on for months or years. But, particularly for misdemeanors, people can take plea agreements and be sentenced to probation or fines, meaning they could be released much sooner.

What isn’t included in those terms is the “silent life sentence” imposed by the collateral consequences Smith is now working to fight. Smith believes if people knew about these consequences, they might be more likely to try to fight misdemeanors and other charges to clear their records completely.

Another consequence of contact with the justice system that disproportionately harms people living in poverty comes in the form of fees associated with involvement in the system — which can include a “booking fee” for the police car ride to the precinct even if your case is dismissed — and fines.

“People who are saddled with these fees and fines are some of the poorest members of our society,” Eisen, of the Brennan Center, said.

While fines are punitive and associated with sentences, fines are meant to help raise revenue to fund the justice system, but this shouldn’t happen at the expense of the people who can least afford it.

“We need to eliminate fees entirely and we need to adequately fund the court system and the judiciary in this country and we need to stop relying on poor people to fund the court for staff,” Eisen added.

“You’re saying that I'm a criminal forever. Ever?"

Fines, she believes, should be based on people’s ability to pay, and avoid sending people into debt, which can lead to further collateral consequences.

“Criminal justice debt is so harmful for many reasons … It's really a barrier to reentry,” Eisen said. “People have this debt even when they’re not incarcerated anymore and it can be hard to pay off while you’re incarcerated when you’re working jobs for 25 cents an hour. Then you leave prison with debt and it’s incredibly hard to successfully integrate.”

And if a person’s criminal record hasn’t already made them ineligible for public housing, that debt can ruin their credit, making it even harder to find housing.

Smith said he is excited to see progress in New York and elsewhere toward eliminating bail. In March, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and state lawmakers passed a bill eliminating cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent crimes. And he is energized by the conversation around reducing prison populations and finding alternatives to prison.

“But what happens when all of those people who come out of prison return to a society where they are still serving a sentence for the rest of their lives?” he asked.

“You’re saying that I'm a criminal forever. Ever? You just judge me by that [part of my life] forever?” Smith said. “Then what is rehabilitation in this country?”

To help raise awareness about these collateral consequences and build a community of advocates and activists, Smith has recently started hosting a dinner event he calls “A Feast for Fair Chance.”

The goal is to encourage people to break bread and break down these issues. Over the course of the evening, Smith tells his story, and walks attendees through a booklet of readings and activities he has created.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith grew up on Nostrand Ave. in Brooklyn. He was raised by a single mother in a home where drug abuse was a problem. Incarceration was the norm in his community, he says. All his uncles and nearly all his aunts have been to prison.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith grew up on Nostrand Ave. in Brooklyn. He was raised by a single mother in a home where drug abuse was a problem. Incarceration was the norm in his community, he says. All his uncles and nearly all his aunts have been to prison.

Michael 'Zaki' Smith grew up on Nostrand Ave. in Brooklyn. He was raised by a single mother in a home where drug abuse was a problem. Incarceration was the norm in his community, he says. All his uncles and nearly all his aunts have been to prison.

He begins by asking attendees — often formerly incarcerated people, friends of formerly incarcerated people, and those who are simply curious — to write about a time they felt they were given a “fair chance.” The goal is to challenge them to think about their own lives, and acknowledge any kind of privilege they had — or did not have — and may continue to enjoy today.

Part of the evening is spent walking through what it’s like to take a plea agreement and be sentenced, only to later find out about the collateral consequences formerly incarcerated people continue to face and how those conditions can encourage recidivism. Before attendees leave, Smith encourages them to reach out to lawmakers and call for laws imposing collateral consequences to be removed, passing around postcards they can use to write letters. But to start with, Smith just wants people to start having conversations.

So far, he and his small team have hosted four dinners in New York City and hope to bring them to Washington, DC, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon. His ultimate aim is to build a movement to remove laws that create these collateral consequences and reinforce perpetual punishment.

“I want to get them to understand why this person may have possibly gone back and forth to prison most of their life,” he explained, “why it’s hard.”

This week Global Citizen is publishing a series of stories focused on the impact of cash bail and the criminal justice system on people affected by poverty. Go to End Bail, Fight Poverty to read these stories.