In 1787, when the United States Constitution was adopted, it didn’t define a federal standard of who was eligible to vote. The thinking was that stages would decide for themselves who was eligible to vote. That meant ballots were accessible to adult, white, male property owners.

Of course, that’s not the case today — many more people have the right to vote. And that’s because of some very famous names — and many, many more who deserve to be. Across the country, they crusaded so we could affix that proud sticker to our lapel each November: “I Voted.”

Learn More: Not Registered to Vote? We Can Help!

Here’s a look at the Americans who fought like hell to make sure you have the right to vote.

Thomas Wilson Dorr (1805-1854)

One by one, from 1792 to 1856, states said you didn’t need to own land to vote, but things got dramatic in Rhode Island. In 1841, the Ocean State still operated under a 17th-century charter that dictated less than half of its adult white males were qualified to vote. Thomas W. Dorr organized a “People’s Party,” that followed a new constitution and abolished voting restrictions. For a time, there were two competing governments, but eventually, the governor had Dorr was arrested. He was found guilty of treason and sentenced to a life of hard labor and solitary confinement. In light of public outcry, the governor pardoned Dorr the next year, and in 1843, the state adopted a new constitution that extended the vote to all tax-paying native-born adult males, including African-Americans.

Read More: These Are the Closest Elections in US History

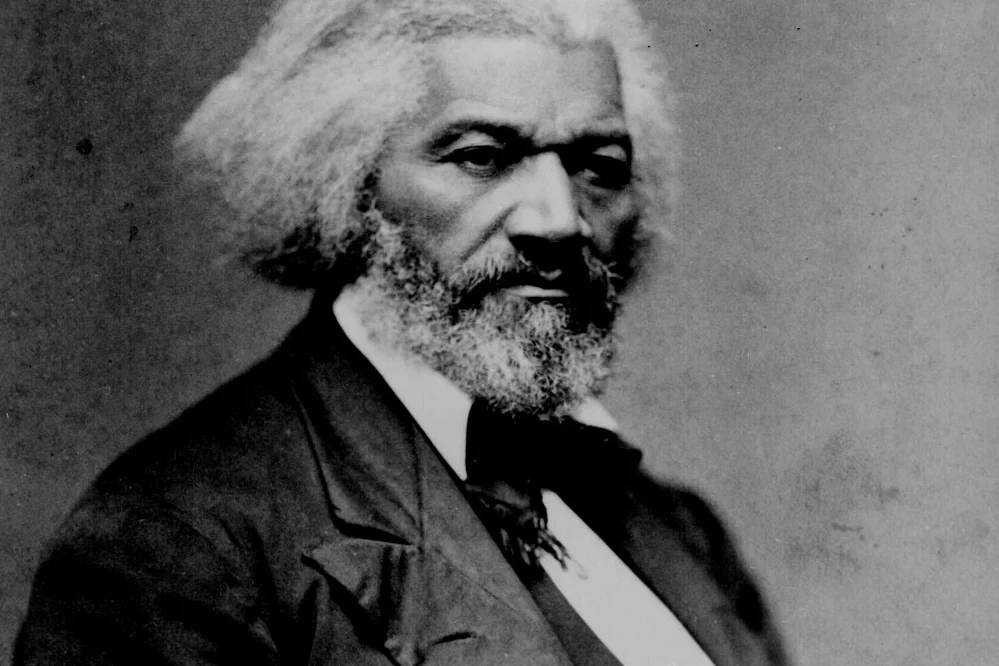

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

In 1865, just days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate troops, abolitionist and social reformer Frederick Douglass was an advocate for equal rights of all people, which included the right to vote. Speaking before the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, he said: “If we know enough to be hung, we know enough to vote. If the Negro knows enough to pay taxes to support government, he knows enough to vote; taxation and representation should go together. If he knows enough to shoulder a musket and fight for the flag for the government, he knows enough to vote ....What I ask for the Negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice.” The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, declaring the right to vote would not be denied "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Lucy Stone (1818-1893)

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone

When it comes to women’s suffrage, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton tend to get all the credit. But Lucy Stone — a 19th-century trailblazer who kept her maiden name and wore baggy trousers under her skirts when she spoke in public — campaigned tirelessly for universal voting rights. Suffragists were split following the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, but Lucy Stone maintained that it was a step in the right direction and continued to work for women’s rights and the rights of all people. In pants.

Learn More: What Is National Voter Registration Day?

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931)

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells

Journalist, suffragist, and all-around badass, Ida B. Wells decried lynchings in editorials, and along with W.E.B. DuBois, was one of the founders of the the National Advancement for Colored People. In a march on Washington for women’s suffrage in 1913, when she was instructed that black women would march in the rear, she “refused to take part unless ‘I can march under the Illinois banner.’” She later ran for the Illinois state legislature, and went on to found the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago.

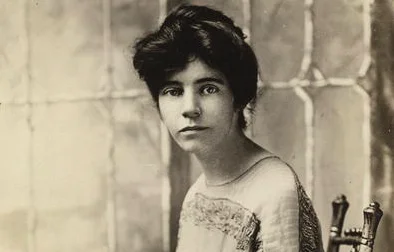

Alice Paul (1885-1977)

Alice Paul

Alice Paul

Called the most radical of women’s suffragists, Alice Paul used civil disobedience to draw attention to the cause, including parades, demonstrations, and a seven-month picket of the White House that lead to arrest and jail-time for Paul and other activists. In 1920, the 19th Amendment granted all women citizens a right to vote, but Paul didn’t rest long. In 1923, she proposed an Equal Rights Amendment. “Men and women,” it read, “shall have equal rights throughout the United States.”

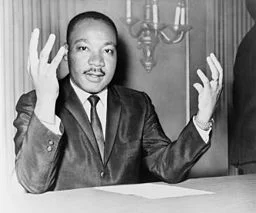

Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968)

Martin Luther King

Martin Luther King

Since the passing of the 15th Amendment, African-Americans — as well as Latinos, Native Americans and Asian-Americans — continued to face systemic barriers intended to keep them from the polls. In early 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., brought national attention to the issue with a voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama. They were met with fierce opposition by Alabama officials, which eventually led to the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. When the march arrived at the state capitol, they were 25,000 marchers strong. Months later in August of 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race.

Ted Kennedy (1932-2009)

The World War II reprise of “old enough to fight, old enough to vote,” resurfaced during the Vietnam War. In Alaska, Georgia, Hawaii and Kentucky, voters under 21 could vote and nothing disastrous had happened. Speaking before Congress, Ted Kennedy reported that 21 as the age of maturity was based on an 11th-century notion of when a young man was capable of bearing the weight of armor. “The medieval justification has an especially bitter relevance today, when millions of our 18 year olds are compelled to bear arms as soldiers, and thousand are dead in Vietnam,” he said. The 26th Amendment was ratified in 1971 and granted the right to vote to citizens of the United States at 18 years of age.