Global Citizen wants to make sure every eligible person casts a vote this fall. Not registered? We're here to help. Be sure to #ShowUp and vote this fall.

Here’s an unpopular opinion: Voting is kind of a pain. You’ve got to look up your polling place and wake up earlier than normal so your boss won’t flip. Or you go after you’ve clocked your eight hours and are forced to delay the already-onerous task of dinner-making. Hangry voting? No thanks. No wonder apathy runs high at poll-time with the inevitable conclusion of, my vote doesn’t matter.

Stop right there.

Research and studies show that policymakers are most responsive to the interests and preferences of individuals who live in districts with high levels of turnout. It’s kinda like what Woody Allen said about showing up: Voter turnout matters.

But if that’s not enough to inspire earning the most ultimate of November status symbols, the “I Voted” sticker, consider that as recently as 2015, a Democrat won the Mississippi House race by “drawing the long straw.” Yup. Even in the race for the nation’s highest office, it often comes down to a hair’s width.

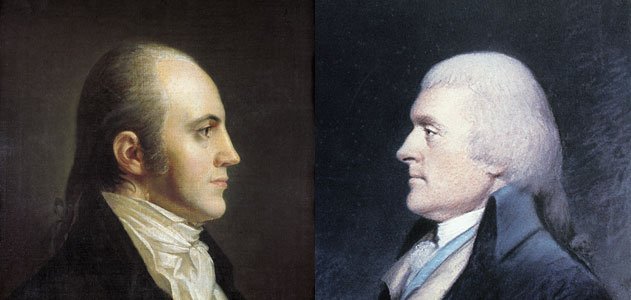

Thomas Jefferson vs. Aaron Burr (1800)

These two weren’t even running against each other — they were running mates. But in the old Electoral College days, each elector could write in two votes for president. The winner got president and the runner-up became VP. But the presidential election in 1800 exposed a snafu in this process. When each member of the electoral college voted along party lines, there was a tie between the two candidates from the most popular ticket and a tied electoral college vote. (In other words: bipartisan politics were at work even back then!) The outgoing House of Representatives had to vote 36 times before Jefferson obtained a majority. This kerfuffle led to the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which calls for electors to make a definitive selection between their choice for president and vice-president.

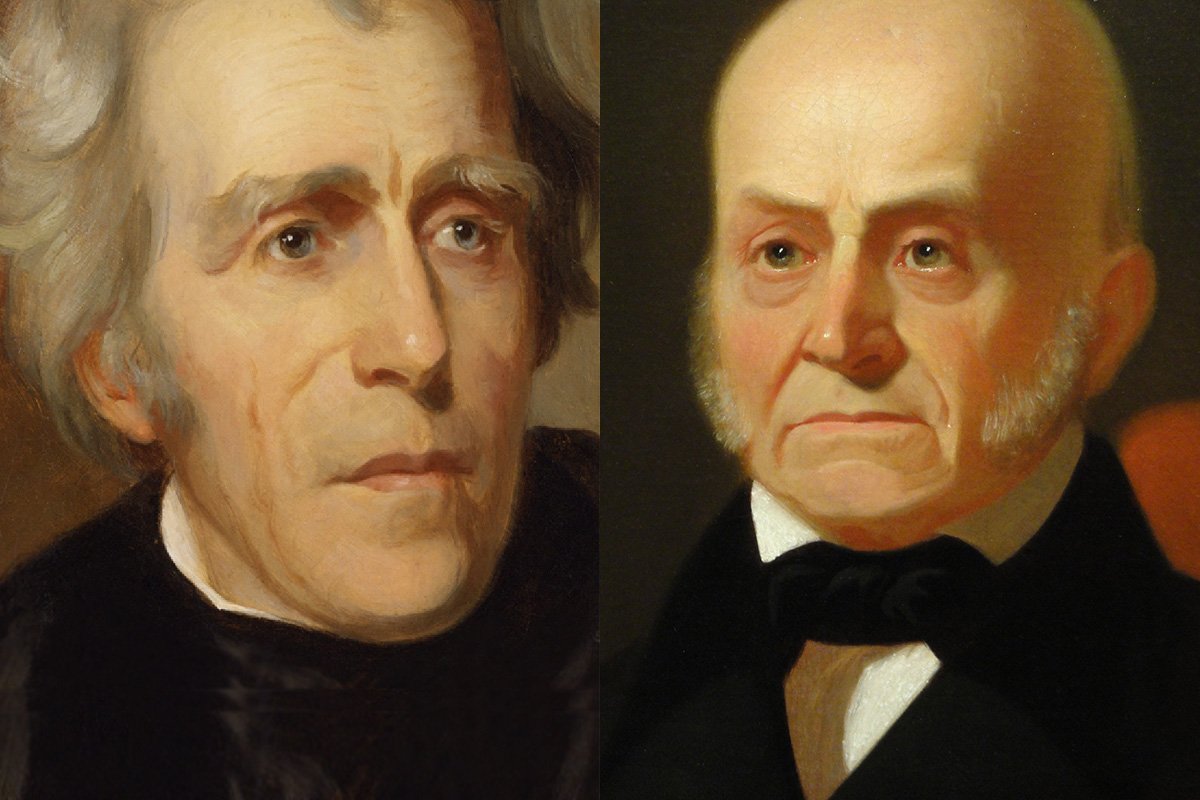

John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson (1824)

Jackson won the popular vote but failed to capture the majority of electoral college votes needed to win. The vote went to the House of Representatives, where the election results were held in the balance by one man. Nearly undone by the pressure, Stephen Van Rensselaer bowed his head to pray, the story goes. When he was finished, he looked up to find a ballot for Adams lying on the floor in front of him. A sign! The House elected John Quincy Adams. But don’t cry for Jackson — he took the spoils when he and Adams went toe-to-toe again 1828.

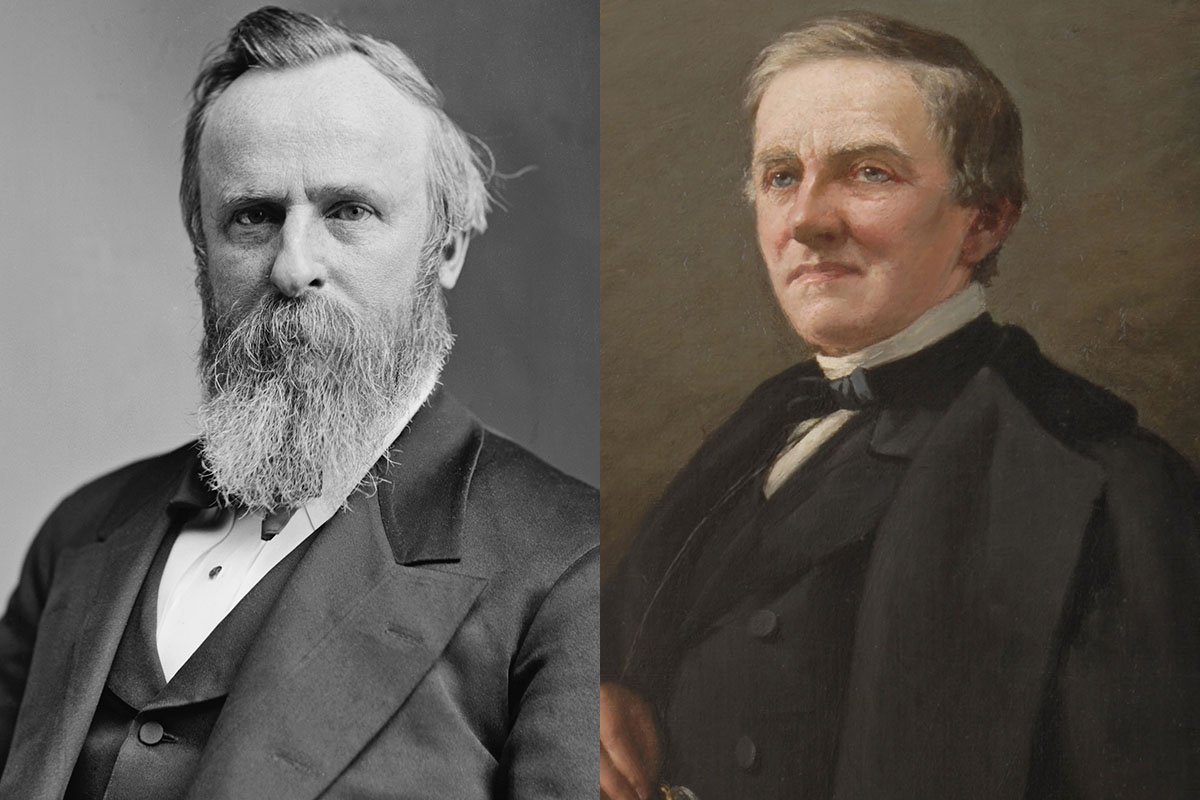

Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This one’s a doozy. With the highest-ever voter turnout (81%!) and and the slimmest electoral college victory, the election of 1876 is one of the most contentious in US history. Samuel Tilden won the popular vote against Rutherford B. Haye, but 20 electoral votes were in dispute. When the states were recounted, the results from South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida were reversed and awarded to Hayes. Democrats — who looked more like modern-day Republicans, and vice versa — refused to accept the results, and a 15-person bipartisan committee was appointed to decide the results. The committee gave the electoral votes to Hayes. Behind closed doors, Republicans appeased the Democrats by agreeing to withdraw troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. This set the stage to reverse gains for African American citizens, including inpeeding the right to vote under the 15th Amendment.

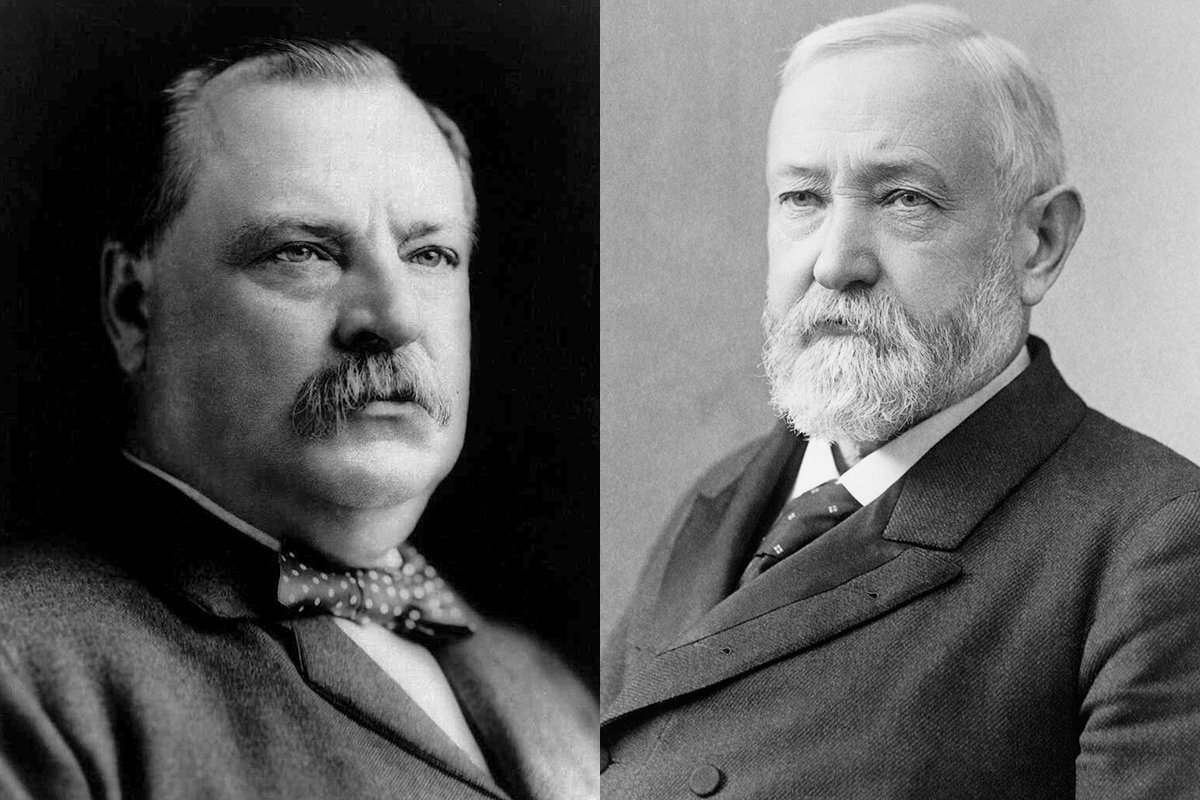

Grover Cleveland vs Benjamin Harrison (1888)

Take three: This was the third election in which the candidate who became the president had not claimed the majority of the popular vote. Grover Cleveland received 90,000 more votes than Harrison — that’s about the population of Tuscaloosa, Alabama — a margin of less than 1 percent. In four states, electoral college votes were won by the same slim margin, but Harrison was declared the winner with 233 electoral college votes to Cleveland’s 168. Historians credit widespread voter fraud and vote-buying for the win, to which Cleveland responded by urging citizens to "restore the purity of their suffrage." It was a clarion call. By the 1892 election, 38 states voted by secret ballot, and Grover Cleveland found his way back to the White House, along with daughter Baby Ruth, the candy bar namesake.

George Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

Both the popular vote and the electoral college vote was crazy-close in this election. Al Gore won the popular vote by a little more than 540,000 votes — about the population of the city of Albuquerque proper — and Bush claimed 271 electoral college votes to Gore’s 266. But there was controversy in Florida that prompted a recount. As the votes were recounted — some counties by hand — and television pundits discussed punch-card-style ballots, never has the milquetoast name “chad” been so central to the cultural consciousness. There were hanging chads, fat chads, and pregnant chads. Bush was eventaully declared Florida’s victor by 537 votes. The race had been even closer in New Mexico, where Gore won by 366 votes.

The moral? Cast your vote or elect not to count.

Voting is a basic democratic right, and it’s important to make sure you’re ready to go to the polls when voting opens in your state. If you’re not registered, you can register here. And if you have friends who aren’t, share the word with them. Learn your state’s laws and get registered — every vote counts.