Tuberculosis (TB), the world’s oldest infectious disease, is also one of its deadliest. In 2024 alone, TB killed about 1.23 million people — more than the combined tolls from malaria and HIV/AIDS combined.

But unlike the urgent flashes of panic that accompany other global health crises, such as COVID-19 and Ebola, TB rarely dominates headlines anymore, nor does it trigger emergency responses from policymakers. Instead, the disease kills steadily as a constant hum in the background of global health, killing more than a billion people since record keeping began in 1882.

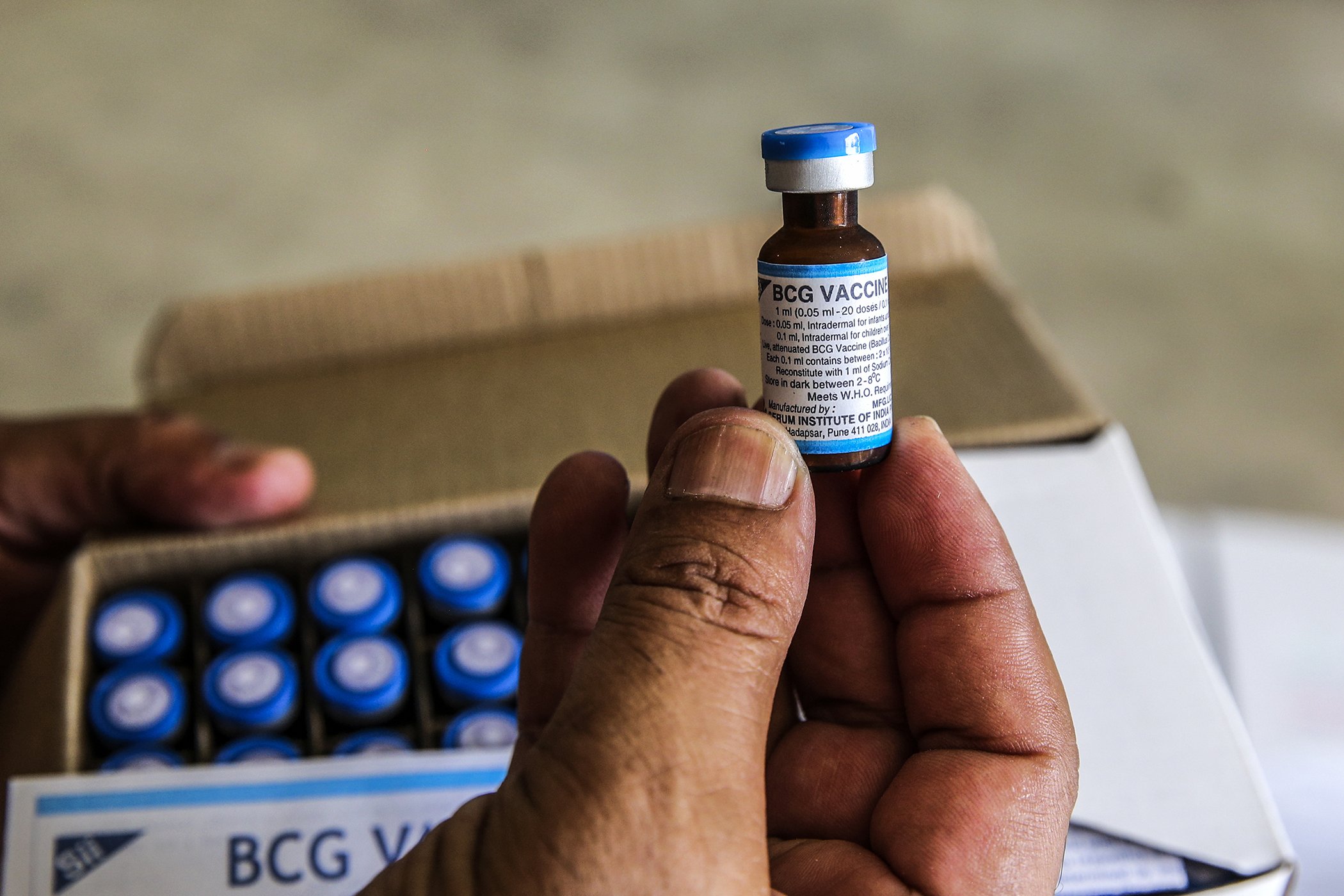

That invisibility reflects the disease’s frustrating story. Today, TB is both preventable and curable, relegated to a memory of a bygone era in most wealthy nations. Yet it overwhelmingly continues to impact low- and middle-income countries. Millions of new cases emerge worldwide each year, but the world hasn’t met a new, approved vaccine since 1921 — and we need one. The only existing one, Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), remains a powerful line of defense for infants and young children, but it offers little protection for adolescents and adults.

The result is a staggering paradox: the world’s oldest infectious disease, against which humanity is armed with effective treatments and basic preventive tools, also remains its deadliest.

Let’s break down exactly how progress has been so slow, but also why, for the first time in years, scientists are cautiously optimistic that this century-long stalemate may finally be breaking.

What is Tuberculosis?

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium that spreads through the air. It can be transmitted when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even breathes. It’s astoundingly common. Nearly one in four people globally (or around two billion people) carry dormant TB bacteria in their bodies.

That statistic can sound apocalyptic, but most people who carry M. tuberculosis never actually get sick. In many cases, the immune system walls the bacteria off successfully. But for roughly 5–10% of people, the infection eventually turns active, allowing it to damage the lungs or spread to the brain, bones, and other organs with devastating consequences. Every year, that means about 10 million people develop active TB.

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that antibiotics transformed TB from a near-certain death sentence into a curable illness. In wealthy countries with robust health systems, new diagnostics and drug regimens, combined with improvements in housing, nutrition, and working conditions, pushed TB out of everyday life.

In much of the world however, the disease never went away. More than 95% of those cases occur in low- and middle-income countries, where the conditions TB thrives in are the most common — these conditions include crowded and poorly ventilated housing, prevalence of malnutrition and chronic illness, and health systems stretched to their limits.

A Vaccine Enters the Scene, But No Cure-All

The BCG vaccine was a genuine scientific triumph when it was introduced in 1921. Developed from a weakened strain of bovine tuberculosis, it dramatically reduced deaths from severe childhood TB. Today, roughly 100 million newborns receive the BCG vaccine each year, saving countless young lives.

But BCG alone could never eliminate TB. For one, its protection wanes with age, offering little to no reliable defense for adolescents and adults — the very populations most likely to spread the disease (babies don’t get out as much, as it turns out). Its effectiveness also varies widely by geography, working better in some regions and not as well near the equator for reasons scientists still don’t fully understand.

As a result, global TB control has relied heavily on treatment rather than prevention. Standard antibiotic regimens, commonly known as the RIPE protocol, can cure most cases of TB relatively cheaply when taken correctly over six months or more. These drugs have saved millions of lives. But they are lengthy, demanding, and can’t take on increasingly common strains of drug-resistant TB alone.

In other words, most of the world has spent the last century fighting the equivalent of an ongoing pandemic with tools from a different era.

What Makes TB It So Hard to Vaccinate Against?

Developing any vaccine is difficult. But developing one for tuberculosis has proven especially challenging.

First, scientists still don’t fully understand what kind of immune response actually protects humans from TB — a major challenge when designing vaccine trials. Unlike diseases such as measles or smallpox, those recovering from TB are still susceptible to reinfection. That means even after successful treatment, patients can still catch it again.

Second, the bacterium itself is unusually resilient. Unlike fast-spreading bacteria like E. coli, M. tuberculosis grows creepingly slowly. Inside the body, it shields itself in a thick, fatty cell wall, hiding asymptomatically for years or even decades as it waits for a weak link in the body’s immune system. Whether because of malnutrition, HIV, diabetes, or other reasons, the balance can eventually tip and dormant TB erupts into active disease — but all that time undetected gives TB an edge in eluding typical treatments, eventually giving rise to drug resistant strains.

These biological complexities help explain why TB vaccine development is riddled with challenges. But they don’t explain why so many people die when treatment options exist.

One Disease, Two Realities

To understand why TB is largely forgotten in high-income countries while a deadly threat elsewhere, we have to look beyond biology and at global health systems.

The contrast is stark. In the US and Europe, governments once deployed mobile X-ray units to detect TB early, invested heavily in prevention, and rapidly expanded access to treatment. In many poorer countries, care has been rationed, diagnostics have fallen behind, and entire categories of patients — particularly those with drug-resistant TB — have at times been deemed too expensive to treat.

As TB declined in wealthy nations, so did the urgency to eliminate it totally. The disease largely impacts communities with the fewest resources and the least influence over global research agendas and funding decisions. As a result, investment in TB research and development has lagged far behind the scale of the crisis.

A Long Overdue Turning Point?

Stéphanie Masika holds her 7-month-old daughter, Altheis, as she receives routine vaccinations, including protection against measles, polio, and tuberculosis, at a health center in Goma, DR Congo, May 2025.

Stéphanie Masika holds her 7-month-old daughter, Altheis, as she receives routine vaccinations, including protection against measles, polio, and tuberculosis, at a health center in Goma, DR Congo, May 2025.

Today, TB vaccine development remains underfunded. Experts estimate about $800 million per year is needed to move promising candidates through clinical trials and into real-world use.

But there’s a big reason to hope for that to change. For the first time in generations, the TB vaccine pipeline is no longer empty. More than a dozen vaccine candidates are currently in development, using approaches ranging from protein subunits to mRNA.

The furthest along of these is M72/AS01E, a vaccine candidate developed by biopharma company GSK in partnership with the Gates Medical Research Institute. In an encouraging 2019 study, M72 demonstrated roughly 50% efficacy in preventing active TB among infected adults — an unprecedented breakthrough.

If successful, M72 could become the first new TB vaccine in over a century, and the first designed specifically to protect adolescents and adults. Its impact could be transformative, potentially preventing tens of millions of cases and millions of deaths over the coming decades. However, recent cuts to global health budgets threaten to slow progress just as this long-awaited achievement appears within reach.

What It Will Take to Change TB’s Story

It’s estimated that even a moderately effective TB vaccine could save millions of lives and generate enormous economic benefits by reducing treatment costs and protecting livelihoods. More importantly, it could help close one of the most striking gaps in global health care based on income.

It’s important to remember that TB hasn’t survived because it’s unbeatable, but because it’s tolerated — and largely unseen by those with the fortune to call it history. A world where no one dies of TB is beyond possible. We already know how to cure the disease, how to prevent its spread, and hopefully someday soon, we’ll have vaccines that stop it before it starts for everyone.

The century-long delay in developing a new TB vaccine reflects global priorities, not scientific limits. The breakthroughs now on the horizon offer a rare opportunity to correct that agenda. Whether the world chooses to seize it will make the difference for millions.