It was while working in a UK research lab that Francisca Mutapi first noticed the other scientists were approaching treatment to a disease she’d known since childhood from a totally different angle.

Mutapi, who grew up in Zimbabwe, was stunned that her fellow researchers weren’t attempting to develop a treatment for children who suffered from schistosomiasis — an infection caused by a parasitic worm that lives in freshwater in tropical and subtropical regions.

Also known as bilharzia, the parasite can remain in the body for years, can damage organs such as the bladder, kidney and liver, and although it is treatable with medication, for many years drugs were only developed for older children and adults.

Mutapi said she was concerned that preschool age children were not being treated for the disease. Praziquantel, the drug that is predominantly used to treat bilharzia, which is classed as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), is used to treat adults and children above the age of six.

“Yet, by the time children got to the age of six they were already ill because they were being infected when they went to the rivers with their mothers, but we couldn’t treat them,” Mutapi said.

Francisca Mutapi uses models at the Natural History Collections to discuss the life cycle of the liver fluke parasite related to bilharzia, in the Ashworth Laboratories of the King's Buildings Campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi uses models at the Natural History Collections to discuss the life cycle of the liver fluke parasite related to bilharzia, in the Ashworth Laboratories of the King's Buildings Campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi uses models at the Natural History Collections to discuss the life cycle of the liver fluke parasite related to bilharzia, in the Ashworth Laboratories of the King's Buildings Campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

She asked her peers why children under six years old could not receive the treatment, and was told that when the drug was developed, it was not tested on younger children.

Mutapi said she was told that the drug, which works in synergy with the immune system, may not be effective in children as “their immune system isn’t well developed.”

“I said, ‘Well, if their immune system wasn’t well developed, childhood vaccinations wouldn’t work because we give them to children under five.’ Then they said: ‘we’re not sure it’ll be safe’. I said, ‘has someone done the studies?’”

Mutapi was told it was “not worth doing the studies” as other researchers believed children were not exposed to freshwater — and thereby the parasites causing the disease.

But Mutapi didn’t relent. Based on her experience growing up in Zimbabwe, she knew otherwise. In 2009, she returned to Zimbabwe to conduct research on children impacted by bilharzia together with Takafira Mduluza from the University of Zimbabwe. She also rallied colleagues in Kenya and Egypt to do the same.

“Low and behold, it turned out children were getting exposed [to the parasites]. Secondly, they did get infections and when they did, it caused a serious disease and the drug we were treating them [those above six years old] with, were safe in [preschool age] kids, so there was no reason not to treat the children,” she said.

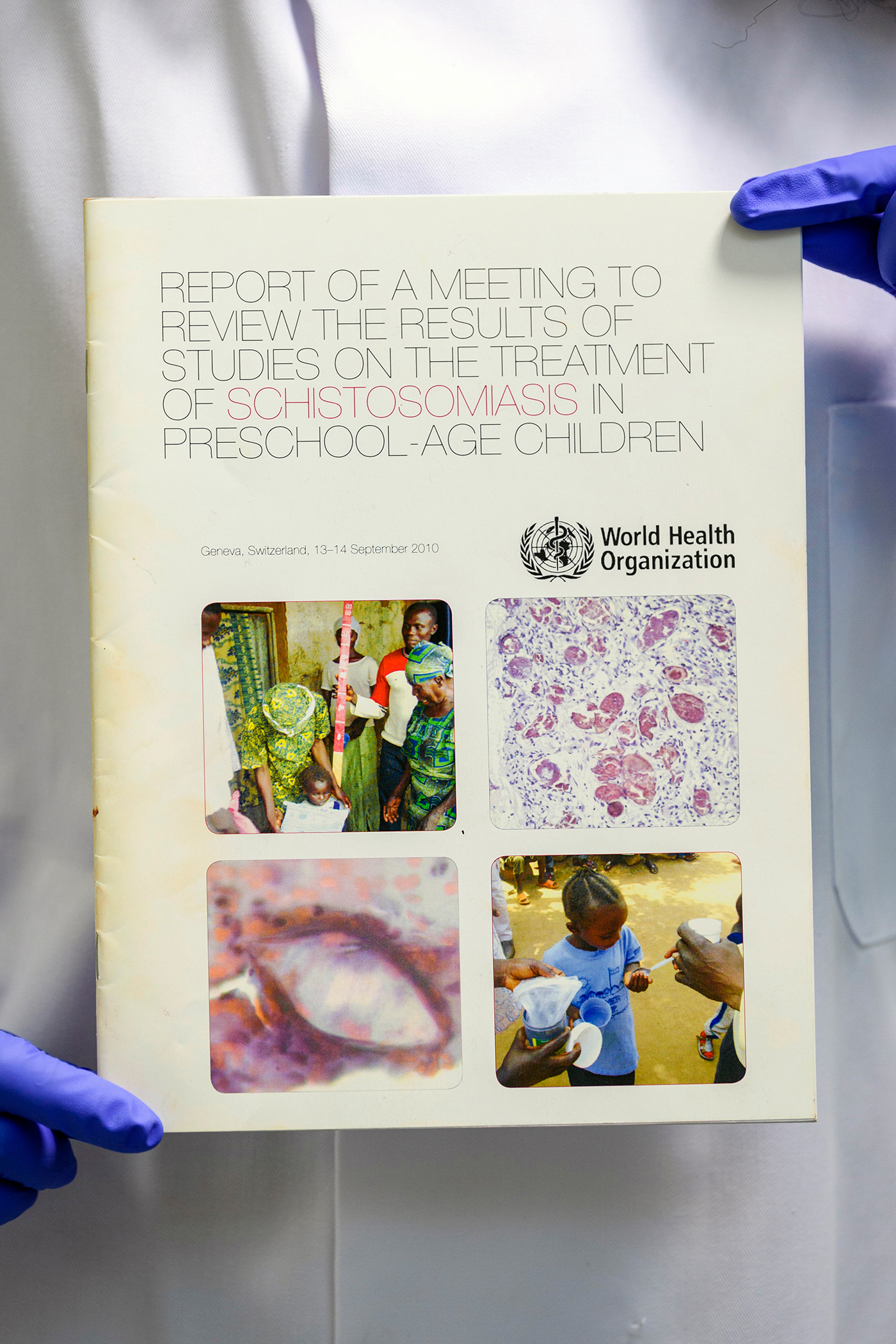

By 2010, Mutapi led the group in taking their research to the World Health Organization (WHO), who after reviewing the findings, agreed with the group’s assessment and decided to permit children under the age of six to receive treatment.

However, the Praziquantel tablets, which Mutapi said are big and bitter to swallow, pose a choking hazard for children. Mutapi and fellow researchers had to give guidance on how best children could consume the pill (by crushing it in water and adding sugar, for instance) and also met with pharmaceutical companies to convene a paediatric formulation of the drug.

The paediatric version, which Mutapi said is in its phase three clinical trials, will likely be available next year, and can change the lives of the 50 million pre-age school children who are infected with the disease.

To put that number in context, Mutapi likes to paint a visual. “If we are to get every child in the world that is affected by bilharzia to stand holding hands, end to end, they would encircle the world one and a half times. That’s how children today need bilzahria treatment.”

Mutapi said Zimbabwean background led her to identify and solve the lack of treatment options for children with this disease.

“I can identify this problem because I am an African who grew up in some of these communities and I know children go to the water,” she said. “It’s a problem, and it’s not a problem that a scientist sitting in a lab in a Western setup can see.”

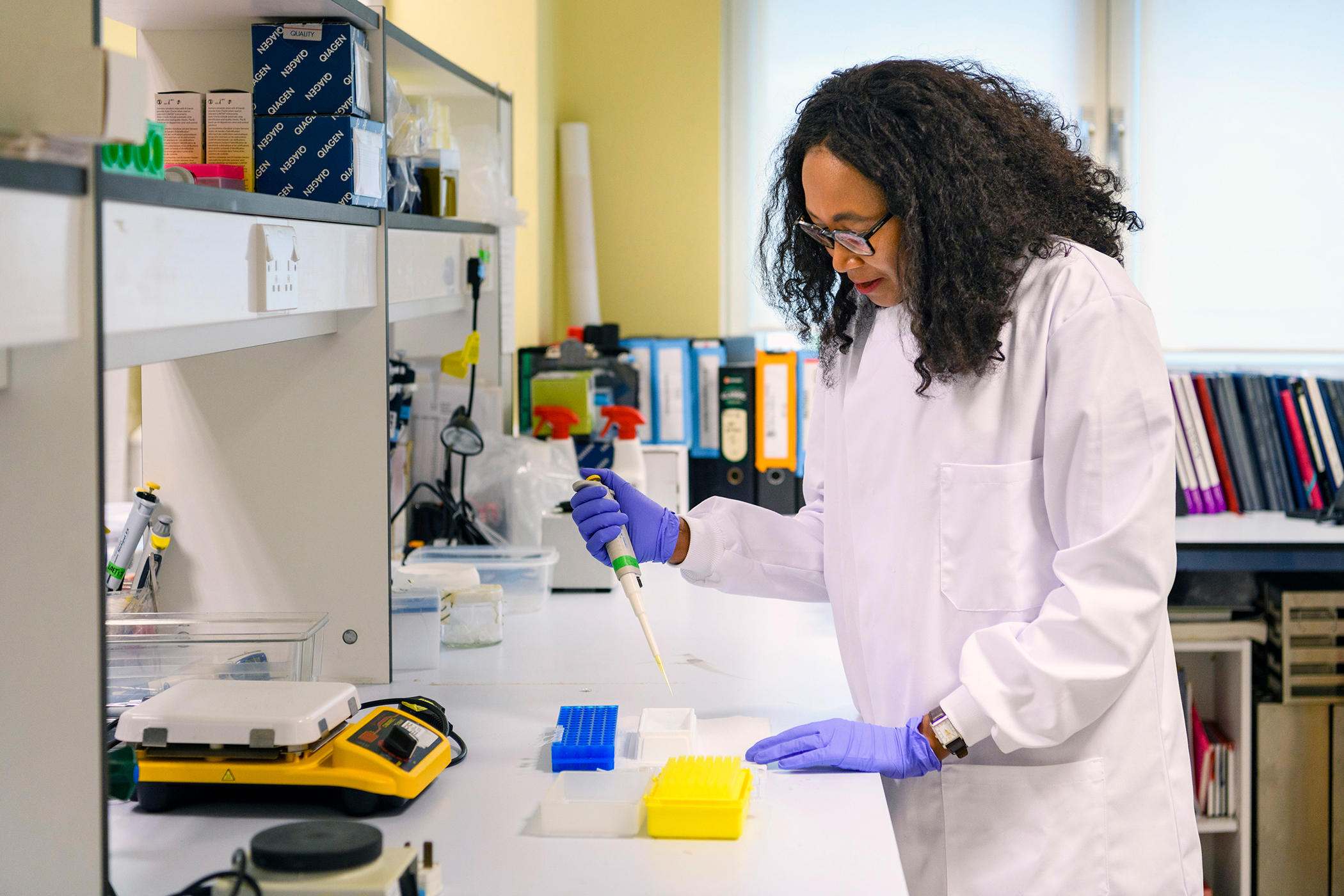

Mutapi, now the deputy director of Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa (TIBA), a global health research unit part of the UK’s National Institute for Health Research, is empowering other African scientists to effectively and sustainably tackle NTDs.

Francisca Mutapi, the deputy director of Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa (TIBA), is photographed in her office at the Institute of Immunology & Infection Research at University of Edinburgh, May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi, the deputy director of Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa (TIBA), is photographed in her office at the Institute of Immunology & Infection Research at University of Edinburgh, May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi, the deputy director of Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa (TIBA), is photographed in her office at the Institute of Immunology & Infection Research at University of Edinburgh, May 19, 2021.

“What we are trying to do is tell African scientists, you know the issues and you know the scale of these problems. What we want to do is [empower] these scientists with the resources and collaboration to tackle context specific local problems of priority.”

In addition, TIBA engages policymakers, heads of state, and pharmaceutical companies in the process, to ensure buy-in and sustainability in tackling NTDs.

“We need everyone on board if we are to make a transformative change in health,” Mutapi said.

TIBA, which works in nine African countries — Ghana, Kenya, Botswana, Sudan, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and South Africa — to find solutions to NTDs, supports scientists in prioritizing the diseases which are most prevalent in their country. While researchers in Uganda are working to find a solution to sleeping sickness, a life-threatening disease caused by parasites, those in Tanzania are researching bilharzia.

Mutapi said her commitment to tackling these diseases comes as she has seen the “transformative power of improving health.”

She said many people focus on bilzahria’s damage to the urinary tract, which leads to blood in the urine, but said the damage is greater.

Her research proves that bilzahria impacts a person’s memory, their ability to develop and learn, movement and hand/eye coordination, and women’s fertility. In addition, it compromises their immune system and makes them more susceptible to other diseases including bladder cancer.

“By treating a single disease you have such an impact on so many aspects of life,” she said.

Francisca Mutapi poses for a portrait on the campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi poses for a portrait on the campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

Francisca Mutapi poses for a portrait on the campus of the University of Edinburgh on May 19, 2021.

The Last Milers is a profile series that highlights the people tackling neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which impact more than 1 billion people globally. By working to ensure equitable access to preventative measures, treatments, and information, these people support the elimination of NTDs in various ways, across different fields. These advocates aim to reach every last mile with necessary health care tools and services.

Disclosure: This series was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Each piece was produced with full editorial independence.