Siobhon Rumurang is writer and educator based in Guåhan (or Guam) working for Nihi Indigenous Media — a production house she describes as building “power and community through narrative strategy and storytelling in the Marianas and Micronesia”. Despite civic space being open in Micronesia, Rumurang reflects on the impact of militarization on her people and the land as a result of Guåhan being an unincorporated territory of the United States. In her own words she shares how war has shaped her home and how she uses her writing to capture and challenge that reality.

I’m Siobhon Rumurang, an Indigenous Chamoru-Palauan writer and educator.

I was born and raised in Guåhan, where my father’s family is from. Though every few years we make sure to be with my mother’s family in Belau, I’ve lived all my life here in the North Pacific islands of Micronesia.

I grew up in a crowd as the youngest of five kids with our maternal grandma living with us. I’m the child of working class teachers and ministers. I spent a lot of time around schools, community events, and service projects.

By the time I was born, my mom was over a decade into her career in special education. My grandma would help watch me at home and I remember following her into the yard where she farmed taro, sugarcane, and banana. I also come from a family of musicians and artists. My childhood was humid, loud, and full — family gatherings outside in the backyard of a cousin’s house, singing for funerals and holidays and graduation parties.

Siobhon Rumurang's work as a writer and educator reflects on the impact of militarization on her people and the land as a result of Guåhan being an unincorporated territory of the United States.

Siobhon Rumurang's work as a writer and educator reflects on the impact of militarization on her people and the land as a result of Guåhan being an unincorporated territory of the United States.

In some ways the seeds of advocacy were planted in childhood, by parents who have always had a strong love for the village.

They didn’t have a lot of money but they had skills and time. I watched them care for our community with what they had — volunteering at prison rehabilitation programs, starting an affordable adult high school, working in suicide prevention with our youth, and teaching courses at the public library for our unhoused communities. I don’t know if I would’ve cared about activism later on without this foundation. Before I developed my own critical understandings of justice and liberation, I knew my love for my home was rooted in seeing community needs and pushing for a reality that was better for all of us.

In occupied territory, writing for me is a second homeland. It’s where I reflect on the impacts of militarization.

Advocacy became more personal for me during my college years.

I was spending a lot of time in postcolonial literature classes, reading Pacific histories, learning about the scale of US militarization in my home. I’d come home for the summer break and get into political discourse with my dad, a history teacher at the time. My brother enlisted for the army. I was 19 years old and reading Microchild, a collection of poetry written by my grandpa’s brother reflecting on Palau’s violent struggle for independence from the US. I was also spending hours on social media feeds following the news of state violence and protests across the nation — Trayvon Martin, Ferguson, Black Live Matter, No DAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline), Standing Rock. Anti-war demonstrations after US airstrikes across the Middle East. I began to see Guåhan’s struggles beneath the heel of militarization in connection with other movements for justice.

When I finished college and returned home permanently, I remember being overwhelmed with news of military expansion plans in Guåhan: mass deforestation, threats to our main water source in the north, sacred sites turned into firing ranges and weapons testing grounds, thousands of marines relocated to our island. So much development, so much money being poured into our island just for our people to be complicit in global war regimes, just to benefit the wealthiest class. The Department of Defense preying on our people in poverty, enlisting them in droves. It was unbearable. All while our hands remain tied as a US territory with no voting power or agency over our own lands. I began working on demilitarization issues because I understood the way war destroys Indigenous homelands and families — here and across the world.

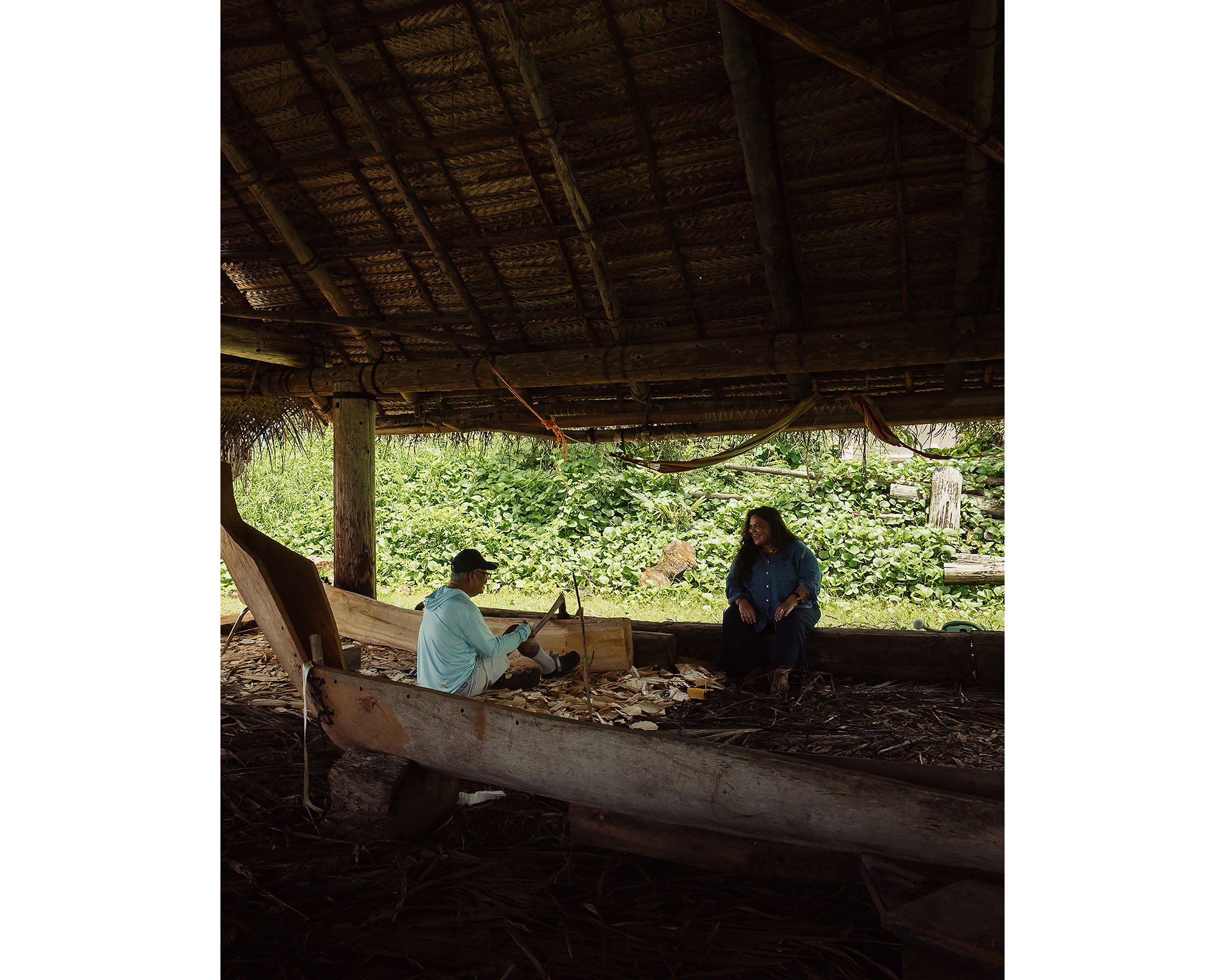

I’m currently a writer and program coordinator at Nihi Indigenous Media

A production house here in Guåhan that supports community storytelling and cultural preservation. in the Marianas and Micronesia. Nihi was established back in 2013 by Cara Flores, founder and Director, after several years of organizing to protect our island and community from the severe impacts of US military expansion and operations on Guåhan and throughout the Pacific that disproportionately impact our Indigenous peoples. Through everything from educational campaigns to animated biographies, short documentary work to music videos and Indigenous language immersion — I get to have a small hand in helping uplift our people’s stories, joy, culture, and collective liberation movements.

Most of my days are spent writing or researching. Working in community-based media is an extremely collaborative environment. When I’m not drafting scripts or pulling references for a project, I’m coordinating with our wide network of Indigenous artists, traditional elders, youth, and community leaders. When I’m not writing for work, I’m making slow but steady progress on my essays and other nonfiction projects. In occupied territory, writing for me is a second homeland. It’s where I reflect on the impacts of militarization and the resilience of Indigenous communities as the land shifts beneath us.

My modes of writing often move between historian, witness, and futurist; it seeks to offer Indigenous peoples a place of reckoning — to exhume what’s been erased, to grieve what can’t return, and to imagine where we will continue beyond futility.

Changemakers need the rest of the world to resist futility, to resist wholesale despair.

This year, I co-wrote an animated series for Nihi called Heroes of Micronesia.

It’s a celebration of influential elders and leaders from our region who were fierce defenders of our homelands, cultures, and peoples. From traditional knowledge keepers and teachers, to activist attorneys and poets, our people come from heroes who addressed the challenges of militarization, colonialism, occupation, and climate change — and loved us enough to protect our homes, to build a different world, and to move us toward liberated futures.

We’ve been able to screen this series in islands all across Micronesia and the broader Pacific, and in classrooms globally. For many of our island audiences, they’re hearing these stories for the first time. And it’s a gift, to be able to empower our people with our own living histories of resistance and revitalization through impossible times. It’s a reminder that we come from greatness, from the beauty and strength of old lands and courageous people.

Siobhon displays Microchild, a collection of poetry written by her grandpa's brother reflecting on Palau’s violent struggle for independence from the US. She read the book when she was 19 years old, a time where advocacy became more personal for her.

Siobhon displays Microchild, a collection of poetry written by her grandpa's brother reflecting on Palau’s violent struggle for independence from the US. She read the book when she was 19 years old, a time where advocacy became more personal for her.

Currently, Nihi is working on a documentary following the indigenous leaders…

…behind the largest case in the International Court of Justice’s history, where islanders took climate change to the world’s highest court and secured a landmark advisory opinion. In the world of environmental justice, this has changed the future of what’s possible for communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis. And we get to be part of telling the story of Indigenous attorneys and frontline voices who led this movement.

Back in 2023, Urgent Action Fund (UAF) was one of the first funders to send relief aid to our organization.

This came after super Typhoon Mawar devastated whole villages in the northern part of Guam. Since then, the UAF Sister Funds in the Pacific have given me incredible opportunities to gather in transnational spaces with other organizers and activists across the globe. Because the UAF convenings are built by, and for, the grassroots world, there’s a real power in the solidarity and knowledge-sharing that takes place in these gatherings. There’s no politics of diplomacy or couching issues in neutral or obfuscating language. We meet and we can be clear about the challenges posed by militarization and violence to our homelands. We can speak directly to funders and explain what needs to change in the colonial process of getting resources to frontlines. UAF has worked hard to create gathering spaces that foster real strength between our movements and I feel so honored to get to be part of this community.

Under the current US administration, I’ve seen how efforts for peace and demilitarization have become increasingly challenging.

Not just in Guåhan but across the US and all its territories. Here in the Marianas and Micronesia, we are working in one of the most militarized places in the world. In 2014, 1 in 8 Chamorus was active or retired from the military. Since then, thousands of Marines have been relocated to the island and hundreds of acres have been cleared for base expansions. We’ve witnessed our homes be turned into testing grounds. And there is no organizing here without navigating strong cultural and national ties within our communities..

There’s an economic and social risk when you choose to be outspoken against militarism — jobs that may not hire you, government grants that won’t fund you, veteran family members that feel ashamed of you. When the US military presence is so interwoven into daily life, disentangling their presence within our communities and trying to reduce our island’s dependence on military-related industries becomes a huge challenge.

Many of the people I’ve worked with are low-income or working class; they are caretakers of large intergenerational families, survivors of violence, and often they are having to hold up their communities with very little resources or access to healthcare. I see my commitment to advocacy as an extension of our obligations to the island and her people — it’s my responsibility to care about the material conditions that threaten our future. We’re part of this work because we can’t opt out.

Siobhon Rumurang is writer and educator based in Guåhan (or Guam) working for Nihi Indigenous Media — a production house she describes as building “power and community through narrative strategy and storytelling in the Marianas and Micronesia”.

Siobhon Rumurang is writer and educator based in Guåhan (or Guam) working for Nihi Indigenous Media — a production house she describes as building “power and community through narrative strategy and storytelling in the Marianas and Micronesia”.

Community leaders and advocates need liveable wages and access to healthcare.

They also need stable housing, institutional support, genuine safety, and connection to the wider world of liberation movements. Activism is long and lonely work if you’re doing it tired, underresourced, and isolated. I’ve had the privilege to become part of grassroots alliances, Indigenous organizations, and transnational support networks that believe our communities most affected need holistic care and resources..

Changemakers need the rest of the world to resist futility, to resist wholesale despair. There’s a kind of cowardice I despise in national conversations around what we can’t bear to witness. That we don’t have the language to hold the scale of global violence. That we couldn’t possibly articulate pathways in, through, or out of this era of political instability. That we’re reaching points of no return. It’s half true and mostly escapism. As an advocate who has benefited from transnational movements and communities, I don’t waste the privilege of sometimes sitting at the world’s grassroots tables — of glimpsing a hundred different possible futures — of progress, setbacks, or adaptation.

There’s always more to lose. There is no finality. What’s still left is not nothing. Someone stays, someone moves money to the frontlines, someone hides, someone else hides them, someone claims the land back, someone trades secrets of escape or infiltration. Somewhere, new forms of life form.

Find out more about Siobhon’s work here. This article, as narrated to Gugulethu Mhlungu, has been slightly edited for clarity.

The 2025-2026 In My Own Words series is part of Global Citizen’s grant-funded content.