When Kwame Amponsa-Achiano recounts the early years of his career working as a doctor in remote areas in Ghana, the rainy season always stands out in his memory.

July and August, which are at the peak of the season, mark a spike in malaria cases.

“You enter the ward and you don't leave,” said Amponsa-Achiano, whose busy work schedule had him frequently skipping meals. “Every five minutes, you are setting up another blood [transfusion] on a child who is almost dying.”

Malaria, which is caused by a parasite, is transmitted through mosquitoes to humans. Symptoms, which take on average of 10 to 15 days to appear, can include high fevers, chills, diarrhea, headaches, and other flu-like symptoms.

If left untreated — even for 24 hours — malaria can lead to serious illness or death.

“I actually suffered both in terms of physical and mental health because we didn’t want to watch children die,” Amponsa-Achiano told Global Citizen. “That’s the kind of disease we are talking about.”

Although malaria is preventable and curable, an estimated 627,000 people died from the disease in 2020, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano (left) walks with a colleague at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano (left) walks with a colleague at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

The WHO reports that the overwhelming majority of cases are in Africa, with the people on the continent experiencing 95% of malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths. Every year, more than 260,000 children in Africa under the age of 5 die from this disease.

In Ghana, deaths due to malaria have been decreasing for years. In 2012, eight people in the country died every day from the disease. By 2020, that number had been reduced to one death per day.

Still, malaria remains a major cause of illness and death in the world, particularly impacting children and pregnant women.

“We’ve come a long way, but [our efforts in combating malaria] are not optimum yet and we have just plateaued,” Amponsa-Achiano said. “Any additional intervention … will be good — and that is what makes us excited about a vaccine.”

Malaria has a significant economic toll as well, representing the highest disease expenditure of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).

For every episode of malaria, patients lose eight to nine workdays and their caregivers lose five days. Since some children contract malaria multiple times per year, this cumulatively leads to a massive economic and workforce loss for their caregivers, Amponsa-Achiano said.

When he was a child, Amponsa-Achiano recalls being so ill that sometimes he would be in the hospital every other week.

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano poses for a photograph in his office at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano poses for a photograph in his office at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

“I lived in a village where transportation was a problem,” he said. “Imagine a 6-year-old [or] 7-year-old boy who is sick, vomiting, and is walking about a six mile journey to the next nearest [medical] center.”

In hindsight, he realized he was sick with malaria. At the time, in the 1980s, he said the interventions to combat malaria that exist now, such as insecticide nets, indoor residual spraying, and the use of drugs to prevent or treat malaria, were not accessible.

“I was fortunate to have survived,” he said. “Quite a number of children died in my village without any cause, and [it] could be because of malaria.”

Now, Amponsa-Achiano, who works for the Ghana Health Service, the service delivery arm of the country’s health ministry, is working to provide children like him with access to a life-saving vaccine.

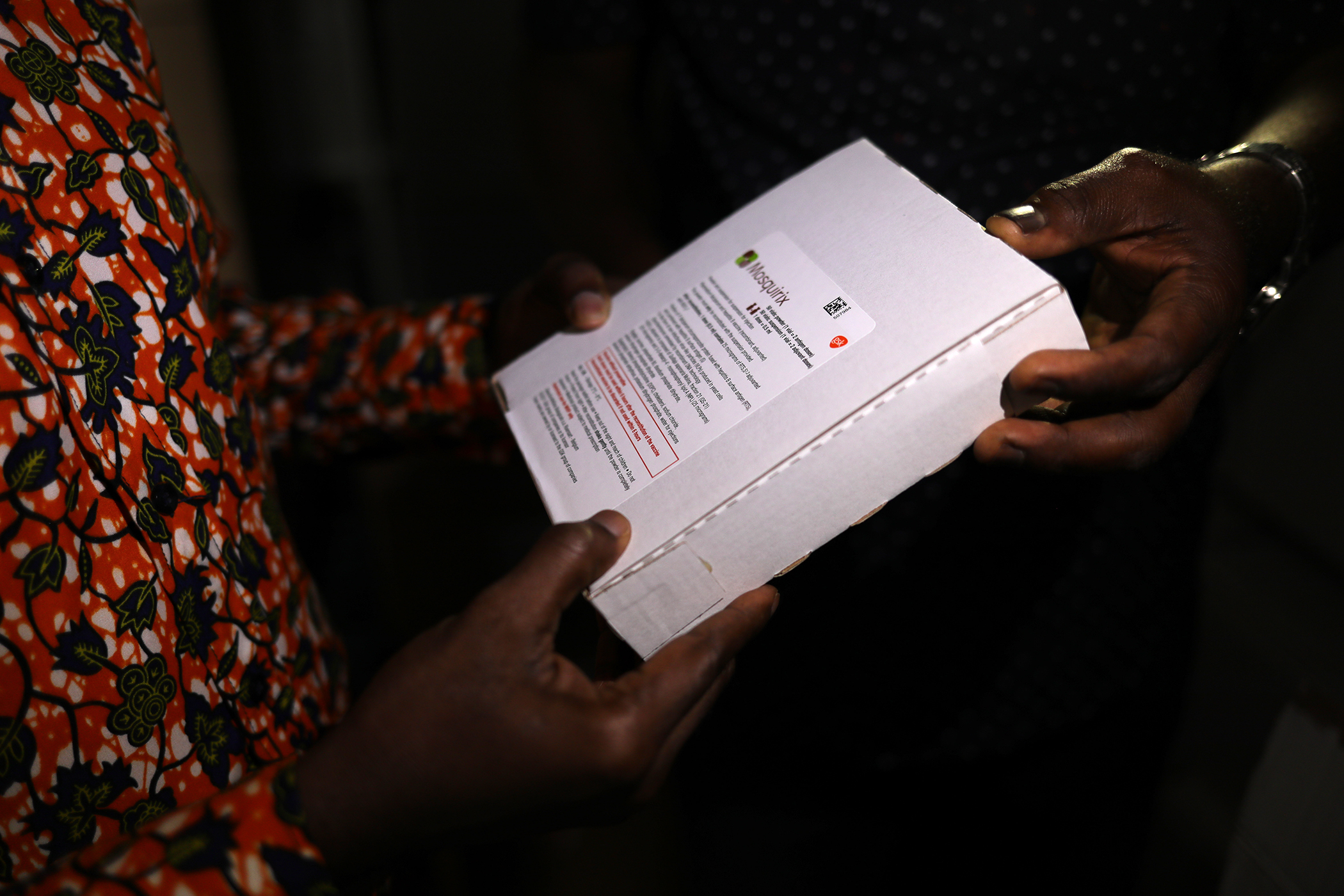

The RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S) malaria vaccine is recommended by the WHO for children living in regions with moderate to high transmission of the disease. The vaccine, with a trade name of Mosquirix, comes after three decades of research and development, and reduces deadly, severe malaria by 30%.

The RTS,S vaccine is administered through four doses in children starting from five months of age and has been hailed as a groundbreaking vaccine in the fight against malaria by the WHO.

However, the international scientific community has raised major concerns with the malaria vaccine evaluation. When rolling it out, the WHO used a process of implied consent rather than informed consent, which means participants were not notified they were participating in a study. This sparked international criticism from leading bioethicists and researchers, one of whom called it a “serious breach of international ethical standards.” The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation also recently announced it would no longer provide funding for the vaccine, in part due to its low efficacy rate, the AP reported.

The Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme, coordinated by the WHO, has reached more than 900,000 children across Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi since 2019.

Since May 2019, when the vaccinations first rolled out in Ghana, 380,000 children have received a minimum of one dose, according to Amponsa-Achiano. He says this figure represents about 75% of all children in the qualifying age category in the country’s seven participating regions (Ahafo, Bono, Bono East, Volta, Oti, Central, Upper East).

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano at a meeting with colleagues at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

Dr. Kwame Amponsa-Achiano at a meeting with colleagues at the Expanded Program on Immunization, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana on July 22, 2022.

If the last two years have taught us anything about global health, it’s the importance of vaccines. The World's Best Shot is a profile series dedicated to sharing the stories of vaccine activists around the world.

Disclosure: This series was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Each piece was produced with full editorial independence.