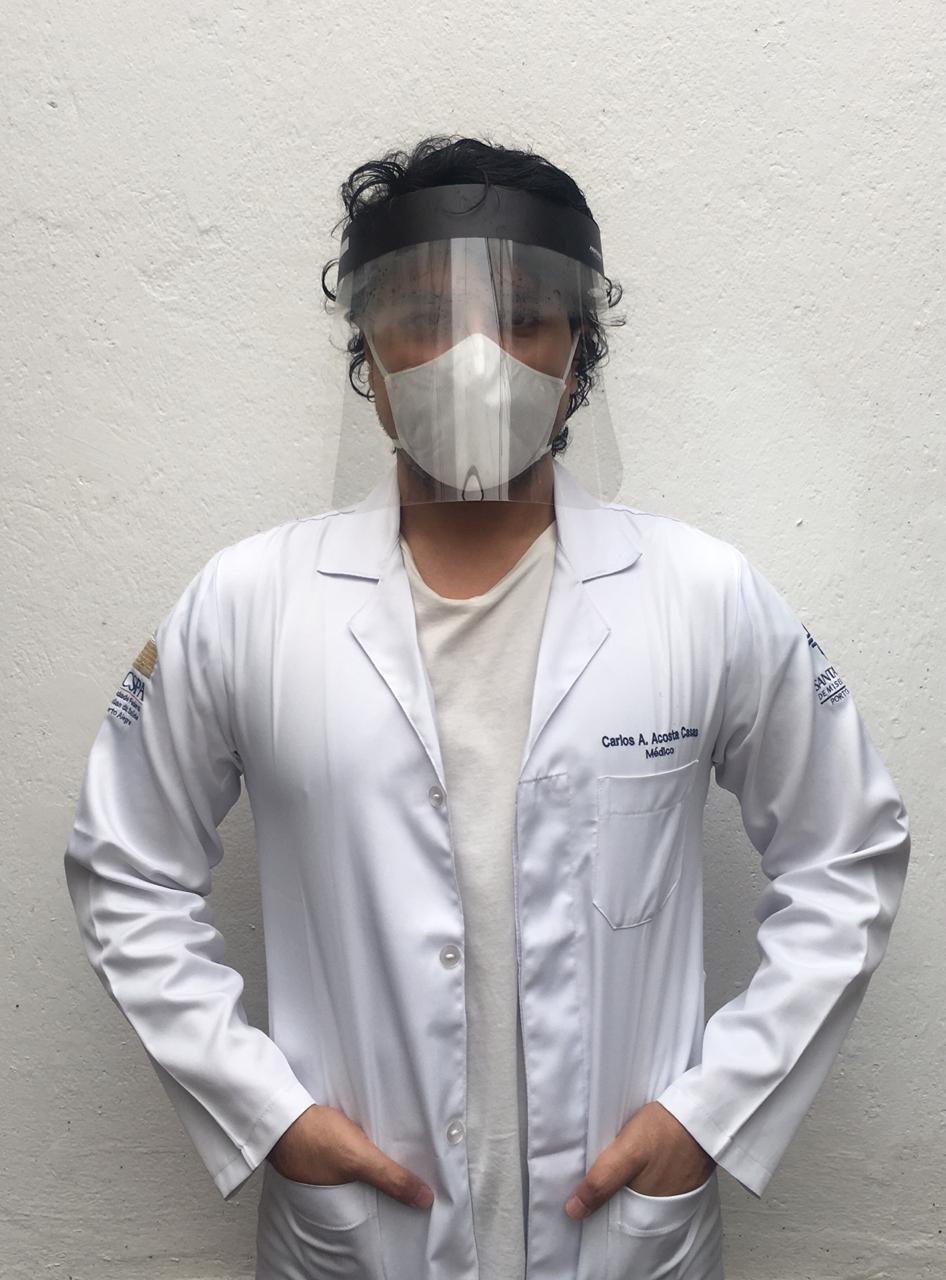

Carlos Acosta, 26, is a junior doctor, born and raised in Bogotá, Colombia, who has studied and worked in Brazil.

He is also a Masters of Public Health candidate at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, a member of the Youth Coalition for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, and Chair of the Global Surgery Network (IniSioN) in Brazil.

This PRIDE month, he shares his experiences of discrimination and injustices for the LGBTQ+ community in accessing good health and calls for this to shape a fairer post-COVID-19 world.

You can read more from the In My Own Words series here.

I was born and raised in Bogota, Colombia and have lived, studied, and worked in Brazil for seven years. As a teenager, I used to fear needing to visit a health centre. At the time, I felt that the main reason I might’ve been sent there was to “cleanse the gay away”.

From Brazil’s inclusion of HIV health care services in the 80s to the first representation of the LGBTQ+ population in its National Health Council in 2006, there have been some major advances made for LGBTQ+ health rights across the country and Latin America. But we still have such a long way to go.

It’s unacceptable that the community continues to be burdened by health inequalities and suffer prejudice, discrimination, and violence that compromises wellbeing.

Across Latin America, young gay men and transgender women are particuarly vulnerable. Recent research by the Regional Information Network on Violence against LGBTI People in Latin America and the Caribbean revealed at least 1,300 LGBT+ people have been murdered in the region in the past five years, with 90% of those deaths occurring in Colombia, Mexico, and Honduras.

The majority of victims were males under the age of 25. In Colombia and Peru, pandemic lockdown measures permiting men to go out on certain days and women on others have exposed trans and non-binary people to a number of cruel attacks.

As has been the case for decades, achieving inclusive health care has felt like an act of defiance rather than a guaranteed human right. Despite evidence indicating that the health vulnerabilities of LGBTQ+ patients are complex, I have experienced how stereotypes are intrinsic in our health models.

It was only on a recent shift that a fellow junior doctor told me he had requested a HIV test to be carried out by a patient of LGBTQ+ identity, without any prior discussions about that patient’s sexual history. It’s not the first time I’ve witnessed exchanges between providers and LGBTQ+ patients being reduced to our sexual practices and unfounded HIV testing.

As leaders begin to build back after the coronavirus pandemic, it's critical they step up to increase awareness of the injustices we as a community face. We exist and we will resist.

The first step on this journey is acknowledging that most health care systems were built based on heterosexual views. From medical education to hospital resources, there was little to no representation of the LGBTQ+ community in decision-making on what LGBTQ+ health care should entail.

We need affirming appointments, comprehensive sexuality education, and a broader understanding of an LGBTQ+ patient’s needs, but this has to be integrated in consultation with the community.

Education and culturally-sensitive training for health workers both play a fundamental role in tackling stigmas and supporting medics to deliver the right kind of care to these populations. For too long, public discourse has perpetuated stigma around LGBTQ+ people and their “clandestine” sex lives. If we are to have any hope in breaking this down, it needs to start in the classroom.

Secondly, there is an urgent need for the international community to invest in and scale up research. COVID19 is highlighting how the higher prevalence of existing health challenges amongst the LGBTQ+ population, such as obesity and cancer, increases their vulnerability to respiratory illnesses.

Studies report that substance abuse is also up to three times higher among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth than hetreosexuals, with research in Mexico linking smoking amongst these populations to the violence they face.

But there is much we still don’t know — especially in my own region. A better understanding of how and why vulnerable and marginalized communities are at risk of developing chronic diseases will have a life-saving impact.

Lastly, any conversations are incomplete without the inclusion of mental health. We know that anxiety, depression, and mood disorders are prevalent in the LGBTQ+ community. In particular, bisexual members and LGBT+ youth (who are more likely to be homeless) are at a higher risk of experiencing mental health challenges.

It is important to consider how COVID-19 has impacted the coverage and quality of services that support the LGBTQ+ community, with funds diverted from NGOs and grassroot organizations. We need to protect and improve these channels of support rapidly.

I hope that one day, health systems everywhere recognize this community as an asset and not a burden. When history for COVID-19 is written, I hope we can say we rebuilt systems based on inclusion and equality. Where all patients, regardless of their sexual orientation, see a visit to the doctor as something not to be feared, or a luxury they haven’t been afforded.

This article was contributed by Action for Global Health UK (AfGH) — an influential membership network convening more than 50 organizations working in global health. Read AfGH's COVID-19 response recommendations calling for the UK government to protect, expand, and improve health systems worldwide.

If you're a writer, activist, or just have something to say, you can make submissions to Global Citizen's Contributing Writers Program by reaching out to contributors@globalcitizen.org.