As a polio vaccination team wound their way on foot towards a row of grass-roofed houses in a small village in Inhambane province, Mozambique, a voice carried on the wind. Mixed with the sounds of children playing and a rooster calling was a radio show. In the most remote corners of the country, radio still reaches listeners.

Nearly 300 miles away, in a bustling building in Maputo, broadcasters like Stela Mapanga lead programming for some 86 community radio stations active across Mozambique’s diverse provinces and languages. In the run-up to the country’s vaccination campaigns, shows with titles like Field of Development and Health and Life, journalists turn their attention to health.

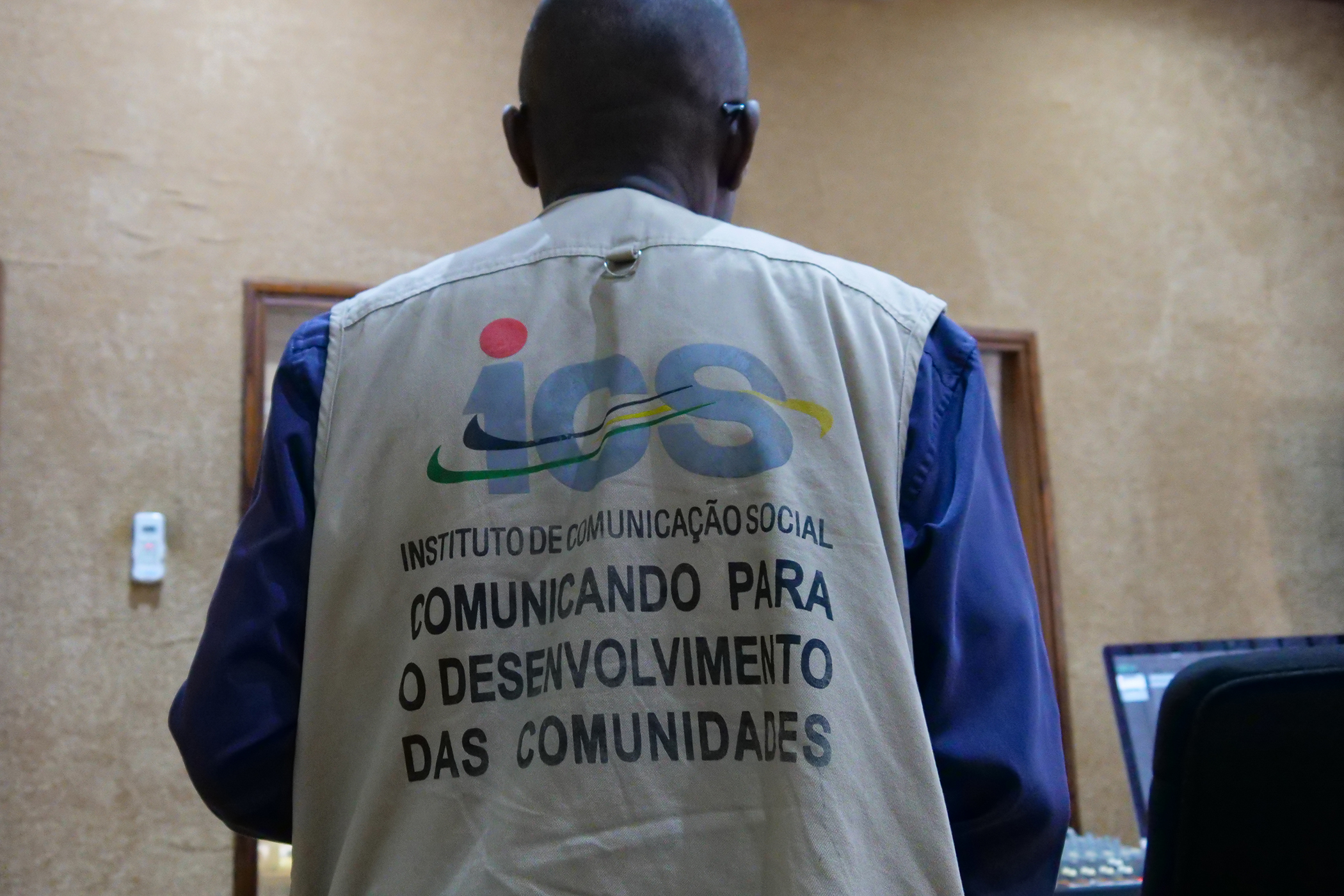

“A major part of the country uses radio,” José Trindade, chief of the technical department at the National Educational Radio and Television of Mozambique's Institute of Social Communication (ICS) told Global Citizen. “Radio can use local languages and is cheaper to establish than TV, so it can be the best media to reach people in Mozambique.” In a country where an estimated 18 million people are reached by community radio, the airwaves are a powerful tool in efforts to stop polio.

Responding to the Return of Wild Poliovirus to Southern Africa

Mozambique conducted two nationwide nOPV2 campaigns in 2025, aiming to vaccinate every child under the age of 10, regardless of previous vaccination status. Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Mozambique conducted two nationwide nOPV2 campaigns in 2025, aiming to vaccinate every child under the age of 10, regardless of previous vaccination status. Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Mozambique has been battling a polio outbreak since 2022, which began in neighboring Malawi when a three-year-old girl was confirmed to have wild polio. Just three months later, Mozambique identified its first case of polio-induced paralysis, with a boy in northern Tete province.

It was the country’s first case of wild polio since 1992, when Mozambique’s 16-year-long civil war, which had widely disrupted vaccination, came to an end. Polio is a highly infectious viral disease, which often spreads through contaminated water and food. It has no cure, and can cause paralysis, most often affecting children under 5.

By the end of 2022 eight more children would be disabled by the wild virus – which was genetically traced back to Pakistan, one of two endemic countries for the disease. Poliovirus variants affected 26 further children across the country as poliovirus re-emerged in southern Africa.

A polio epidemic was declared and Mozambique’s Ministry of Health began both targeted regional and national vaccination drives, working with UNICEF, the World Health Organization and other Global Polio Eradication Initiative partners to deliver two drops of the oral polio vaccine to every child. The country’s wild polio virus outbreak was closed in May 2024, and vaccination has continued against the variants, using the nOPV2 vaccine.

Making Waves with Polio Messaging

Reaching every child is no small task in a country with a large geographic area, at times a lack of infrastructure and many extremely remote communities. Vaccinators must navigate localized conflict in the northern Cabo Delgado province, internally displaced populations, high turnover across six bordering countries and the impacts of climate change – while both cyclones and conflict have also damaged the regional radio equipment used to inform communities about teams’ arrival.

Polio workers ride a motorbike in Inhambane, Mozambique, during a national campaign in June 2025. Motorbikes are used for social mobilisation ahead of campaigns and by vaccination teams in rural areas to raise awareness. Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Polio workers ride a motorbike in Inhambane, Mozambique, during a national campaign in June 2025. Motorbikes are used for social mobilisation ahead of campaigns and by vaccination teams in rural areas to raise awareness. Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Within this complex environment, Mozambique’s extensive community radio network at ICS is a “strategic ally in health promotion,” said Denizia Pinto, UNICEF social behavior change coordination and polio outbreak response, who also leads communication training with journalists.

“In the polio response, we adopt a multichannel approach to reach different audiences in both urban and remote areas,” she said. This ranges from television adverts to text message alerts and even loudspeakers on the back of motorbikes. “Community radio, in particular, plays a critical role as a trusted medium, which is closely connected to rural communities and capable of broadcasting information in local languages.”

As well as broadcasting in Mozambique’s official language of Portuguese, presenters at ICS reach the other half of the population who speak one of the country’s 40-plus local languages, including Ndau, Sena and XiTsonga. Broadcasters work in tandem with ICS field teams, reinforcing messages shared by mobile units working with megaphones in communities with limited radio reception ahead of the vaccination campaign. A public-private partnership ensures the word spreads further across other stations.

Every Tuesday, Mapanga’s program on the country’s largest radio station tackles health topics, from diseases like cholera and malaria to healthy eating. Ahead of two national rounds of polio vaccination in June and July 2025, which saw up to 92% coverage, star guests on ICS radio were doctors and healthcare directors, as the conversation turned to polio.

“I personally produced a programme where I discussed the consequences of the disease and ways to prevent it,” Mapanga said. “I emphasised the vaccination campaigns, saying that all parents, guardians and carers should be aware of them, to take their children to be vaccinated. I stressed that vaccination is the only means of prevention.”

Programmes on stations like Rádio Comunitária Mocuba put health messaging into everyday language, give details of where to access vaccines, feature expert interviews to address misinformation, and perhaps most importantly, include a phone-in section for questions. “In the provinces too, through community radio stations, we always have space for interaction,” says Mapanga, who has even interviewed a guest who came to visit their offices following a callout.

Communicating the case for vaccination has become more important than education around the disease itself. As the outbreak response reached its 11th campaign, and some parents questioned why their child needed repeated doses, presenters asked interviewees to explain how boosters worked. Meanwhile slogans and adverts ran between radio shows, saying: “The vaccine is free, safe and should be taken even by children who have already been vaccinated before. It reinforces immunity against polio.”

Mobilising for Change

Radio is part of a broader community outreach program which has accompanied Mozambique’s outbreak response. Ahead of campaigns social listening exercises – consultants attending routine community meetings through to social media monitoring – seek to sense the mood on the ground, identify any upcoming barriers to vaccine acceptance and see who the current trusted voices on health in the community are.

Signage outside a health centre offering routine vaccinations alongside the June 2025 polio campaign reads: “Polio causes infantile paralysis and has no cure. Vaccinate your children now.” Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Signage outside a health centre offering routine vaccinations alongside the June 2025 polio campaign reads: “Polio causes infantile paralysis and has no cure. Vaccinate your children now.” Image: Lucy Fulford for Global Citizen

Understanding the landscape and prevailing attitudes in this way means that polio messaging doesn’t speak in one voice to everybody, but is customized to each community, and presented by people that they know and trust.

When Mozambique switched to under-15 polio vaccination due to the demographics of cases last year, it required a change in communications to the regular under-5 campaigns. “Instead of our key audience being parents or caregivers, they have some power over decisions,” Pinto said. “They have opinions. So we directed messages to them.”

This year, inclusivity has been a big focus. “Mostly our health messages are directed to mothers, but we know that fathers have a decisive influence for vaccination,” said Pinto. “We are trying to put it boldly, that this is for fathers. It's a collective responsibility to vaccinate the kids.” This featured in a training for radio journalists on how to integrate gender in their conversations, as well as how communities can report suspected paralysis cases.

When monitors check the quality and coverage of polio campaigns, they ask how people heard about the vaccination. Recent data showed 90% of those surveyed had heard about the campaign in advance, with community radio to be among the top three or four sources across the country. Back on doorsteps in Inhambane province, when vaccinators asked parents if they had heard about the polio campaign, some said they’d heard from neighbours, some from clinics – and others from the radio.

Editor’s Note: This reporting was made possible through the United Nations Foundation 2025 Press Fellowship on Individual Reporting on Polio. It is a part of Global Citizen’s grant-funded content through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.