"Pandemic preparedness will always be about people's access to the most basic of health care systems.”

That’s Dr. Stephanie Williams, Australia's Ambassador for Regional Health Security, on the significance of robustly investing and strengthening public-health systems to reduce the chance of future pandemics.

Without that investment, once-in-a-generation global catastrophes like COVID-19, and its widespread socio-economic impacts, could become considerably more common, she said.

Global Citizen recently spoke with Williams, who also leads health security and vaccine access initiatives with the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security, about the Indo-Pacific region’s response to COVID-19, how countries like Australia have helped its neighbours and why universal health coverage is at the core of global health security.

Global Citizen: Is Australia doing enough to help combat COVID-19 in the Indo-Pacific?

Stephanie Williams: Since COVID-19 emerged in late 2019, Australia has been side by side with countries in our region. We've offered health and social protection assistance, big economic packages and contributions to other really important bilateral programs that contribute to people's health and well-being across the region.

In 2020, we made contributions globally to CEPI, COVAX and FIND, and announced a $523 million Regional Vaccine Access and Health Security Initiative for the Indo-Pacific. Over $300 million [in Australian aid] was pivoted for health and economic assistance. In 2021, we are providing direct health and financial support in Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Timor-Leste for their COVID-19 outbreak responses. We've just sent a large package of support to India. We're there every step of the way.

What are the main challenges when it comes to vaccinating people in the Indo-Pacific region?

The first challenge has to be global supply and equity of supply. There are also challenges in the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines and the uptake in the country.

We have complemented COVAX deliveries through weekly sharing of our domestically manufactured AstraZeneca doses with Fiji, Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea and will soon share doses with the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. We’ve also offered to share domestically manufactured doses with other Pacific island countries when they're ready.

We're doing our bit in the region to increase the supply, although we recognise that much more needs to be done.

What are the most pressing secondary COVID-19 impacts faced by the region?

We have countries in the Pacific that closed themselves to the world. As a result, they have little to no COVID-19. But also, as a result, they're experiencing severe economic hardship caused by a lack of movement of people and goods.

Then we have other countries who, say in Southeast Asia, have had good control for a long time. But again, there are now varying responses to outbreaks in that region with varying measures of lockdown.

Broadly, the ongoing secondary impacts include impacts on health service supplies, economies, education and women and girls — who face the most disadvantaged in their access back to school and the economy.

What have been the biggest positives in regards to the Indo-Pacific’s response to COVID-19?

The Indo-Pacific has done remarkably well. I acknowledge that when I say that there's significant outbreaks in Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and Fiji. We've seen an evidence-based response throughout Southeast Asia, particularly in Vietnam and China, and with varying degrees in Cambodia and Laos.

Leaders saw the threat and used evidence and experience to minimise the impact in their countries. The closure of Pacific island countries has meant many have been able to sustain a COVID-19-free status. The fact that small parts of the world remain protected is a real positive in the current environment.

Knowing what we know now, how can the region prepare to ensure a pandemic of this scale is never seen again?

Public health approaches to infectious disease are the bread and butter of pandemic preparedness and response. But public health is underfunded in so many countries, as are health systems generally relative to GDP.

Pandemic preparedness will always be about people's access to the most basic of health care systems and their ability to access the information, the prevention and the services they need. One of the big changes we need to make is reminding ourselves that people and universal health coverage are actually at the core of global health security.

What would you say to individuals in the region who are hesitant to receive the jab?

In 2019, the World Health Organization put vaccine hesitancy on their list of the top 10 major global health threats.

We need to be helping governments and helping health partners understand the reasons behind different uptake or willingness levels in their countries, and that will be through surveys, through talking, through understanding.

I think it’s good to have questions — it's important to say, “What is the benefit of this to me? What are the risks?” It's important to seek out credible and trusted sources of information when you have those questions. I use the World Health Organization and Australia’s National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance as trusted sources of scientific and public health advice.

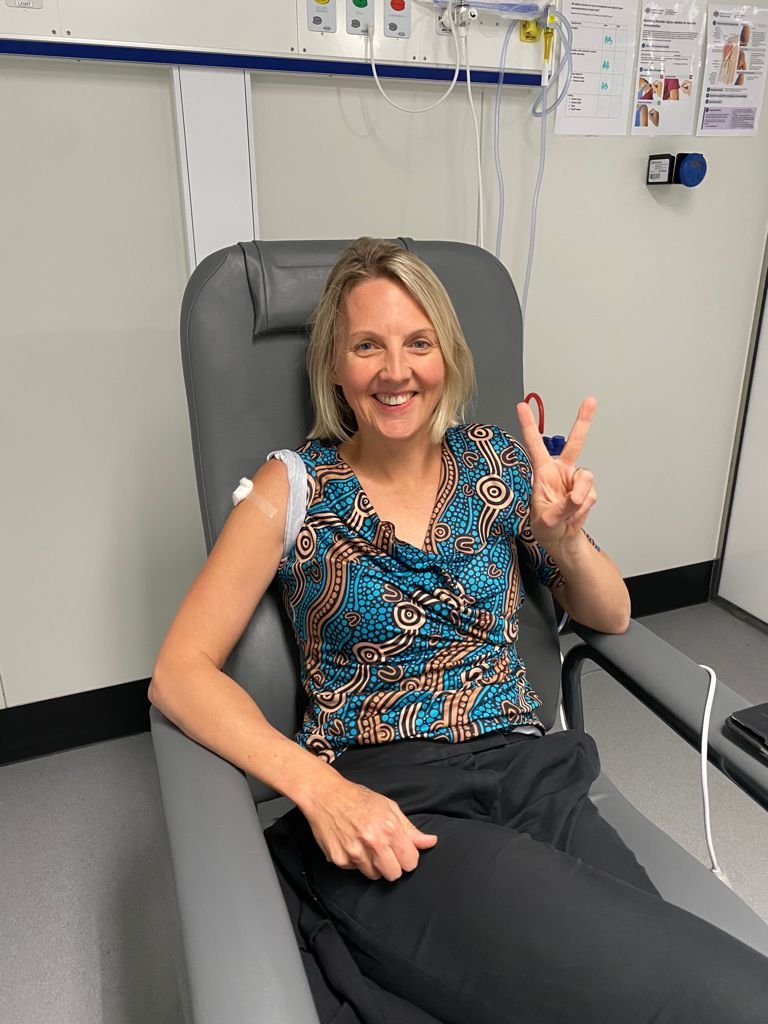

Have you had the jab? What motivates you personally to get vaccinated?

I have had the jab and, at the core, I've had it because I really love being alive. [The vaccine] is a tool that will save my life. It will prevent an infectious disease that we have no treatment for, which we know kills many people. For me, it's a very easy decision because I have complete trust in the science, trust in the process and then trust in the importance of prevention tools being available.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.