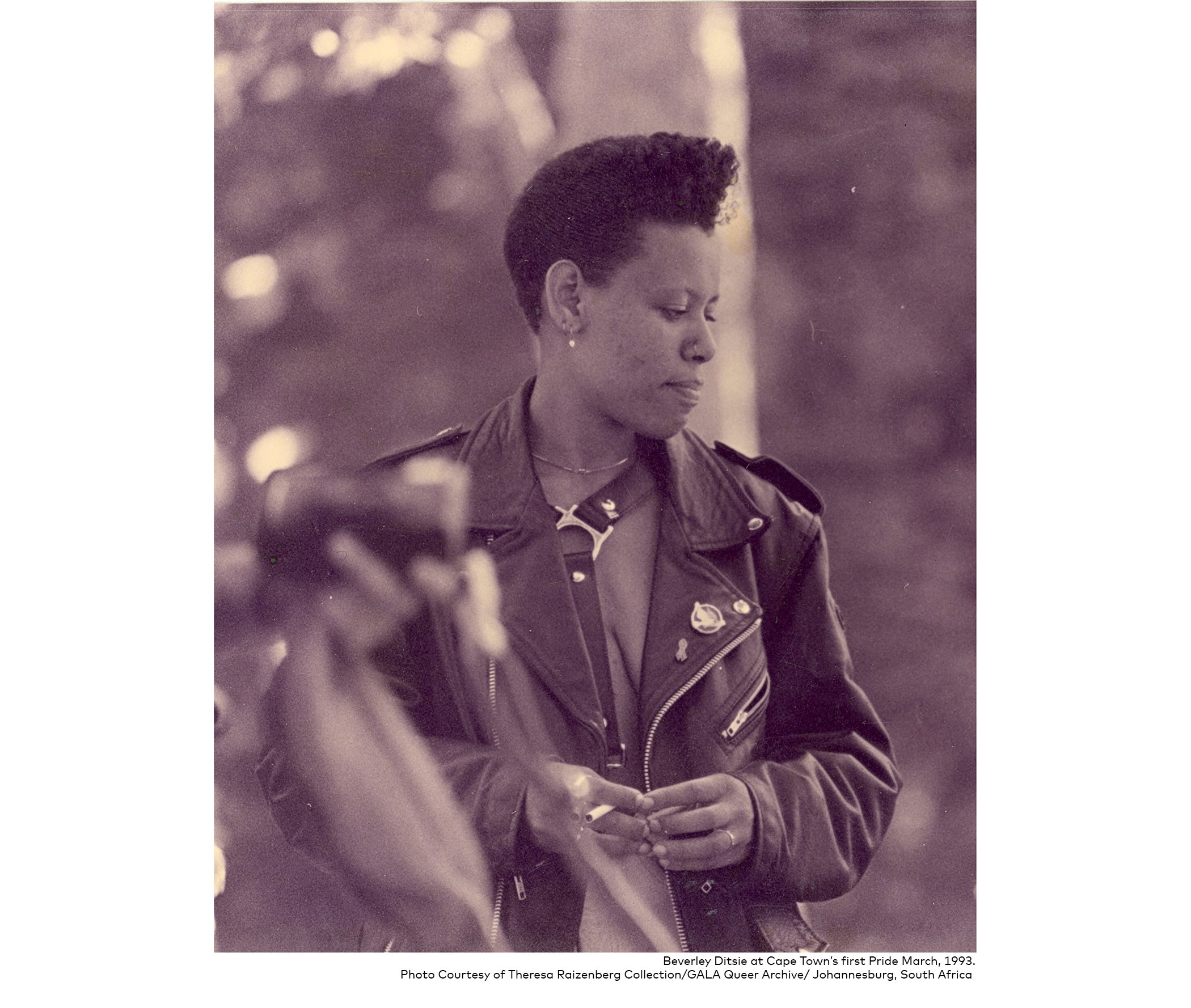

Beverley Ditsie is a filmmaker, LGBTQ+ activist, and one of the founders of the first Pride March on the African continent in 1990. She is an alum of the first multiracial LGBTQ+ organisation on the African continent called the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of Witwatersrand. Ditsie is also the first lesbian to ever address the United Nations at the fourth and final UN World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. In 2019, she was conferred an honorary doctorate by Claremont Graduate University in California for her work in fighting discrimination both in her home country of South Africa and abroad.

Here, she reflects on the recent spate of horrifying crimes against LGBTQ+ people in South Africa, the power of women and community, and the work that still needs to be done to bring freedom and safety to all.

You can read more from the In My Own Words series here. You can also learn how to take action for Generation Equality and #ActForEqual here.

“Outrage as Aubrey’s Boshoga’s killing suspected to be another LGBTI+ hate crime.” (31 May 2021)

“KZN police arrest suspect for murder of lesbian woman Anele Bhengu.” (13 June 2021)

“Lulama Mvandaba murdered in Khayelistsha because she was a lesbian, says family.” (14 June 2021)

"Update: Anger over man burned in car’s boot — speculations of homophobia.” (19 June 2021)

These are all headlines published in South Africa over the past month. Of course, many more siblings have been murdered this year. I chose the most recent, also because I would not be able to fit everyone on this page. This excludes many who have been beaten, raped, burned, terrorised — those who do not make the headlines.

Many of us wonder, which one of us is next?

While homophobia is not state sanctioned in South Africa like it is in many other countries on our continent, while we in fact have a constitution and a Bill of Rights that is lauded worldwide for its inclusivity, there is no commitment to address or to stop this scourge — not from the government or the institutions that have been created for this very purpose.

Someone on social media wrote that this is reminiscent of the mid-'90s, when these murders made headlines almost on a weekly basis. I remember because I was there. I was almost a statistic myself, and that is why I was one of the people who stood up to educate and to fight against this evil.

I grew up in a maternal home, surrounded by mothers, sisters, aunts, and grandmothers. I was a strange but happy child growing up — light-skinned with funny-coloured eyes that made me stick out everywhere I went. I always attributed the stares to the fact that my mother was a well-known superstar; but as I grew up, what made me stick out was the fact that I'd been known in my neighbourhood as a boy.

Having grown up surrounded by women, I didn’t know nor understand that I had to be different anatomically to define my gender in the way that I felt. I knew, however, that I was not a girl. Not in the conventional way that girls were supposed to be, to feel, to want. And since I was not a girl, there was only one other way to be. I was very blessed that my family and my neighbourhood accepted my identity.

The only significant male influence in my life was my grandfather, who was illiterate yet so curious about everything, and he brought the world to my sister and me. He brought home books, broken toys, drawing paints and brushes, canvases, mini English-French and English-Spanish dictionaries. In our four-room home in apartheid South Africa, where education was not a priority for a Black child, we could say hello and goodbye in more than 10 languages by the time we were 5 years old.

By the third month of school, I had already read the entire year’s worth and I was bored silly. I remember having to dumb myself down and pretend that I didn’t know the answers just to protect myself.

As I grew up, I had to pretend a whole lot of things for the sake of self-preservation. I would watch the powerful women in my family, women who just got on with things, doing everything that was apparently only assigned to men, totally change their behaviour when a man walked into our home. The subservience, the pandering, the pretending to be weak and stupid was so confusing to me.

I began to understand that this was all a performance of gender. When I asked my normally rational and intelligent mother what was going on, her response was: “One day, when you are all grown up, you will understand. I was also a tomboy once.” I grew up, but I never understood it.

So I kept questioning. These questions gave rise to my early defiance and ultimate activism.

When I grew older and it became clear that this wasn’t just a "passing phase," I was told to lie about my identity. I was told to hide it by "pretending to be with a boy." I was told that I should "just make a baby and at least fulfill society’s expectation of my womanhood." Many aunts told me that this is what they had to do, that this is what everyone does.

I understood that I had two choices: either deny my truth by lying and pretending to be something I was not, or live my truth but do it in absolute secrecy. My spirit would not allow me to do either. To live in the margins of society would have meant living in shame, as though being myself was wrong. I have never, ever, felt shame for being me. So I went for the only option that made sense to my teenage self. I searched for those who lived their truth openly.

The first Pride March in Johannesburg was conceived after the realisation that we needed to reclaim our truth and demand our rights to be treated with humanity. We were visible, we were loud, we were fearless at a time when we should have been most afraid. But we believed in the power of solidarity and collective resistance.

At that Pride March in 1990, my mentor, friend, and comrade Simon Nkoli said: “I am Black, I am gay, I cannot separate myself into secondary or primary struggle…” This was our introduction to intersectionality. I clearly understood, even at that young age, that my oppression is multidimensional and cannot be contained in a single narrative. To be seen as anything else is to pretend that we are not borne of, and do not live in, the same oppressed, underserved communities as everyone else.

Over 30 years later, the situation is still dismal. "Struggle fatigue" is a term many of us understand well. Activism is unpaid and ungrateful labour, and so many of us left the space to the younger and more enthusiastic activists so we could focus on our personal lives.

What we found instead is that we left a major vacuum — a vacuum that was filled with myths, misinformation, and even more misunderstanding of who we are. We now find ourselves in the clutches of some of the most intense homophobic and transphobic attacks we’ve experienced in a very long time.

It's no wonder these hate crimes are on the rise. Rumours and untruths about the LGBTQIA community, and the so-called sanctity of the "traditional family" — the cisgender, heterosexual model with the man as the head of the family — are nothing more than a continuing attempt to hold onto power and control that is fast being undermined. Colonisers arrived with their racism, their capitalism, their patriarchy and changed the fabric of our societal values, our connections to our non-gendered spirituality, our entire way of life with Ubuntu as the cornerstone of our existence. They enforced the patriarchy by demonising the feminine, and in the process eradicated everything that would undermine their ultimate goal of dominance.

And our people lapped it up, even when evidence of queer existence was staring them in the face — from our non-gendered languages to our many matriarchal lineages. Making it seem as though our many different genders are a new concept. An anomaly. Meanwhile, we have always been here.

Our erasure, or even the continuing narrative of queer lives being miserable, serves the agenda well because my existence as a safe, secure, and in fact thriving gender non-conforming lesbian undermines the myth of cis-hetero-patriachal way of life as the be-all and end-all of all life.

For me, community is what gives value to our lives. This is why I’m still alive, after so many attempts to have me killed.

My grandmothers adore me, and being the pillars of our community meant that others would listen to them. So when I was being attacked, first verbally and then physically, one word from my grandmother and the community came out to my defense. My community gave me, and many of us even before the beginning of His time, my personhood.

In this context, the dehumanisation of queer people — the de-personalisation — is relatively new, and it’s happening as a result of patriarchal indoctrination and the erasure of our existence and who we’ve always been as African people. That’s why we are being killed with such impunity.

I think a lot about our murdered siblings.

How they must have felt in those moments before their death, as they were being beaten, raped, burned, brutalised. I think about their families, too. Some of the families that were themselves so homophobic their queer kids could not come out to them, or they came out but were never accepted nor affirmed. Families who themselves bullied, harassed, or terrorised their children in an attempt to heterosexualise or control their gender and expression. Families who have been so ashamed of their children that they would want to hide the motive for the murder as it would confirm their child’s "abhorrent" sexuality or gender and expression.

I think about how many of us have been to funerals of friends, lovers, siblings, and listened to family members and their chosen preachers speak of their murdered child as being to blame for their own brutalisation — or even worse, speak of the murder as God’s punishment. And we would sit in silence and furious respectability as we were told that we would suffer the same fate unless we conform.

We need to talk about how complicit our families are in our brutalisation, allowing the cycle of shame and victim-blaming to continue.

Family belongs to community, and community takes its cues from family. We need to go back to real community engagement that sees us as people. We need to take back our lives by engaging our families and educating our communities. There are many more human beings than there are homophobes. So the more our families, friends, allies, and communities speak out against this scourge, the more the evil is isolated and shamed.

So please speak up.

We need you and your Ubuntu to stop this madness.

If you're a writer, activist, or just have something to say, you can make submissions to Global Citizen's Contributing Writers Program by reaching out to contributors@globalcitizen.org.