After the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021, hundreds of thousands of people attempted to flee the country. Dominating news headlines and social media channels, the world saw a majority of the population crowd airports and swarm to the nation's borders in a desperate attempt to escape life under the Taliban, a regime known for its strict interpretation of Sharia Law which previously held control of Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001.

While leaders of the Taliban insisted they would be more tolerant this time around, setbacks began almost immediately. Education suffered as the militant group refused to grant girls access to secondary schooling, while independent media outlets were forced to close or broadcast for the Taliban.

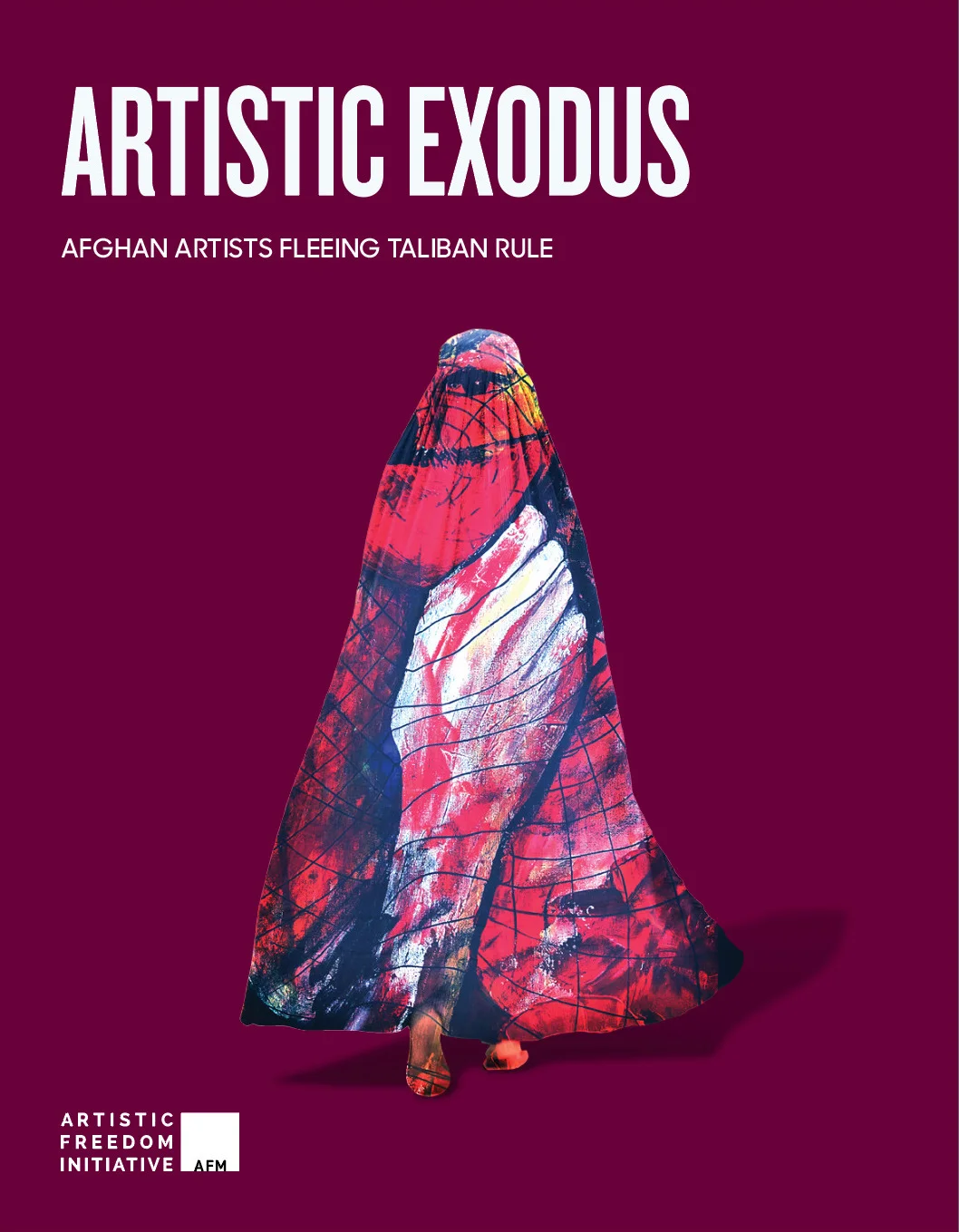

Since the 2021 shift in regime, as everyone has struggled to adjust to this new normal, Afghan artists continue to face harassment, intimidation, and even arrest as the Taliban enforces an ultra-conservative interpretation of Sharia Law, prohibiting the creation of visual art that depicts living beings and most forms of music. Painters, musicians, curators, and cultural workers who have spent their lives enriching and preserving Afghan culture have been forced to cease their work or go underground to avoid persecution.

“Since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, the vast majority of the arts and cultural sector has been completely decimated,” Sanjay Sethi, co-executive director of Artistic Freedom Initiative (AFI), told Global Citizen.

How Artistic Freedom Initiative Stepped In

Founded by immigration and human rights attorneys in 2017, AFI provides legal services and resettlement assistance to artists deemed at-risk in their home countries, whether due to government censorship of artistic narratives or threats to marginalized identities. Since its founding, the organization has taken on over 2,000 cases, helping artists and their families relocate to safer places to practice their art.

In the early days of the organization, AFI received just a handful of applications from a variety of countries each month. But within four months of the Taliban’s return to power, that number quickly rose to more than 3,000 applications from Afghanistan alone, making the country a special focus.

“Artists would send us pictures of what was going on in Afghanistan,” Sethi said. “We'd see demolished instruments, some destroyed by the Taliban, others destroyed by the artists themselves due to fear of what would happen to them if they were discovered."

In response, AFI launched its Afghan Artists Protection Project (AAPP) devoted to helping resettle Afghan artists who no longer see a future in their home country. In addition to providing pro bono legal services and relocation assistance, the organization helps Afghans secure opportunities to continue and showcase their art through concerts or exhibits, preserving their culture globally even as it is suppressed at home.

“These aren’t just issues of freedom of expression — a lot of times, it’s about cultural preservation if something were to happen to the artists themselves or their particular art form,” Sethi said.

Sharing Afghanistan’s Musical Tradition

For many forced to flee the Taliban’s restrictive policies, practicing art is a bittersweet way to feel close to their homeland and keep its culture alive from abroad. That’s particularly true for Mashal Arman, an Afghan woman who left the country when the Taliban first rose to power in the 1990s.

Arman and her mother moved to Switzerland when she was eight years old, after the Soviet army’s withdrawal from Afghanistan led to an ensuing civil war outbreak between mujahideen rebels. Her father had stayed behind to continue running a music school he co-founded.

“It was a big tragedy when the Afghan mujahideen destroyed the school that my father built with his colleagues,” Arman told Global Citizen. “They came into the school and they destroyed and burned all the instruments.”

Eventually, Arman’s father joined the rest of the family in Switzerland. Arman grew up playing the Afghan folk music that flowed through her family’s blood even while studying Western music traditions. Coming from a long line of Afghan musicians who were part of the country’s media landscape for decades, Arman has fought to keep Afghan music alive even while settling permanently in a country far from home.

Today, she is a singer and composer who has linked up with AFI as part of their Heritage & Exile concert series, which showcases exceptional female musicians living in exile. Organized by AFI’s Geneva office, the series highlights the importance of music in communicating identity, displacement, and cultural resilience, featuring artists from Afghanistan, Iran, and Ukraine. For Arman, joining AFI’s Heritage & Exile series is a way she can further the push for cultural preservation.

“I want to create a positive link to my roots in Afghanistan through music, something not related to politics. I want to keep the musical tradition I've inherited alive, because otherwise it is totally disappearing,” Arman said. “This music is so rich and reaches so far back in time. When something is this good, you can continue building on it so it can grow and evolve.”

The Canton of Geneva supports the series by providing free concert tickets and employment opportunities to recently resettled Ukrainians and Afghans in Switzerland. Thanks to this backing, non-artists who are part of their country’s diaspora can enjoy the concerts as well.

The Disruption of the Creative Economy

For many Afghan artists, the Taliban’s return in 2021 threatened a familiar pattern. The country has a rich history in creative expression across film, music, and other forms of media. But the de facto authority has made it clear they would not allow non-Islamic art and culture to be associated with Afghanistan.

Two artists AFI helped relocate previously worked on restoring the Buddhas of Bamiyan in the Bamiyan Valley, two large statues built in the 6th century initially destroyed by the Taliban in March 2001.

Once situated along the Silk Road where traders from across Africa, Asia, and Europe traveled to exchange goods and ideas, the Bamiyan Valley hosted travelers of various backgrounds who brought their cultures and religions to Afghanistan, including Buddhism.

Their destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan was symbolic. The Taliban initiated a call to destroy the statues after they rose to power, along with any other artwork representing living figures.

“The reason the Taliban didn't want those Buddhas to be displayed or to be intact is because it showed that Buddhism had some roots in Afghanistan or traveled to Afghanistan, and it affected their ability to control historical narratives,” Sethi told Global Citizen.

The erasure of the country’s cultural history, along with a dismissal of the creative arts in general today, is a detriment to the people of Afghanistan. Not only are Afghans disconnected from their roots, but artists in particular are unable to engage with their cultural heritage. Local economies suffer, as well. Without support to create and share their work with the world, the entire country loses an increasingly important way to grow in the 21st century.

According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the creative economy — which includes the creation, production, and distribution of goods or services that rely on creativity and intellectual capital — plays a pivotal role in overall economic growth, particularly for developing nations. In fact, UNCTAD and the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimate that the creative industries generate an estimated $2.3 trillion annually and support 6.2% of global employment.

In the three years since the Taliban’s return, Afghanistan’s economy has declined by 27% and has only recently begun to show modest signs of growth. New investments from foreign aid have dipped, while an estimated 9.5 million people are severely food insecure. And with more women pushed out of formal employment, their labor participation is estimated to be just 5%, preventing them from securing their independence, limiting household incomes and the country’s economic growth.

By intimidating artists and effectively tying their hands behind their backs unless they flee, Afghanistan is falling behind in the creative economy at a time when other countries benefit from the sustainable development, diversity, and economic growth it fuels.

How Can Global Citizens Take Action to Support Artists in Exile?

Around the world, the civil liberties that foster artistic freedom are under threat.

From Afghanistan to Iran, authoritarian groups silence creative communities to alter their countries’ narratives,prevent critics from speaking out, and maintain power. In Hungary and the US, biased policies effectively censor the arts, especially if they promote diversity as a strength or refer to LGBTQ+ identities.

As long as censorship persists, the true potential of the creative economy will never be achieved. High-income countries with more flexible economic resources may be able to sidestep this problem, but low-income nations will only fall further behind.

To support at-risk artists and preserve cultural traditions, it’s critical to engage with and amplify the work of displaced artists — whether through providing opportunities or rehearsal space to artists, attending exhibits or performances, sharing their stories, or supporting initiatives like AFI — to ensure their voices are heard, not silenced.

Global Citizen also recently launched the Music Economy Development Initiative (MEDI) — a collaboration between Global Citizen, the Center for Music Ecosystems, and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) — aims to harness music's power to create jobs, boost incomes, and strengthen communities. If you haven't already, follow Global Citizen for more updates on how to get involved.

Take action with Global Citizen to protect freedom of expression globally, and stand in solidarity with artists in exile today.